“STRIKING OUT” SATAN.

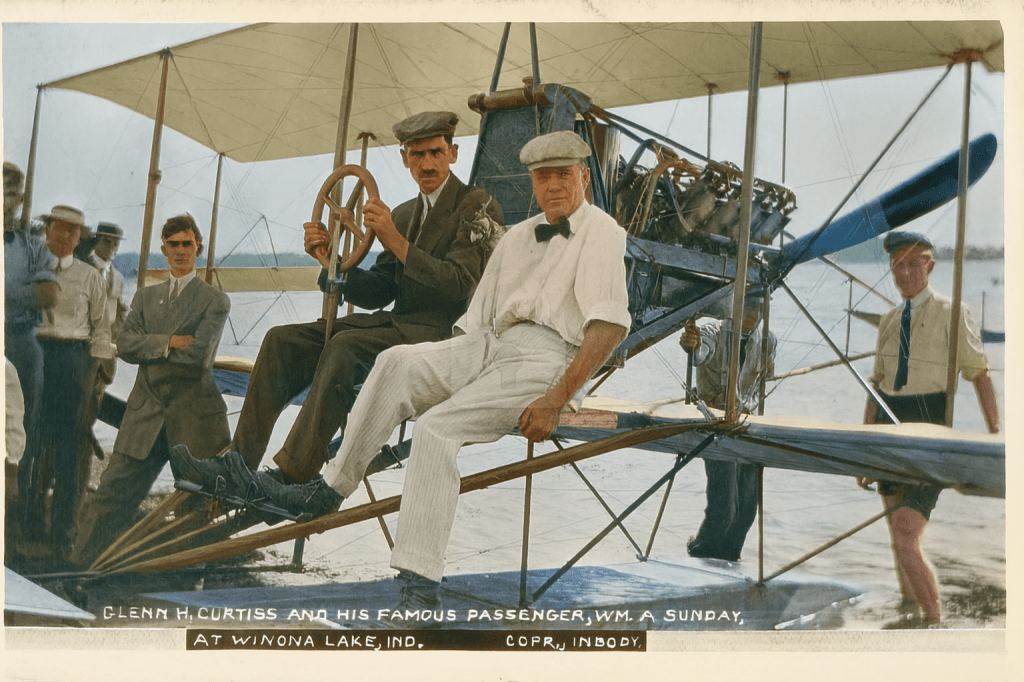

BILLY SUNDAY, THE NOTED BALL TOSSER, TURNS EVANGELIST.

The Famous Centre-Fielder Addresses a Large Crowd at Farwell Hall – He Didn’t Even Allow the “Father of Sin” to Reach First Base – Advising His Hearers to Watch Their “Error Columns” – Forty-eight Converts Made.

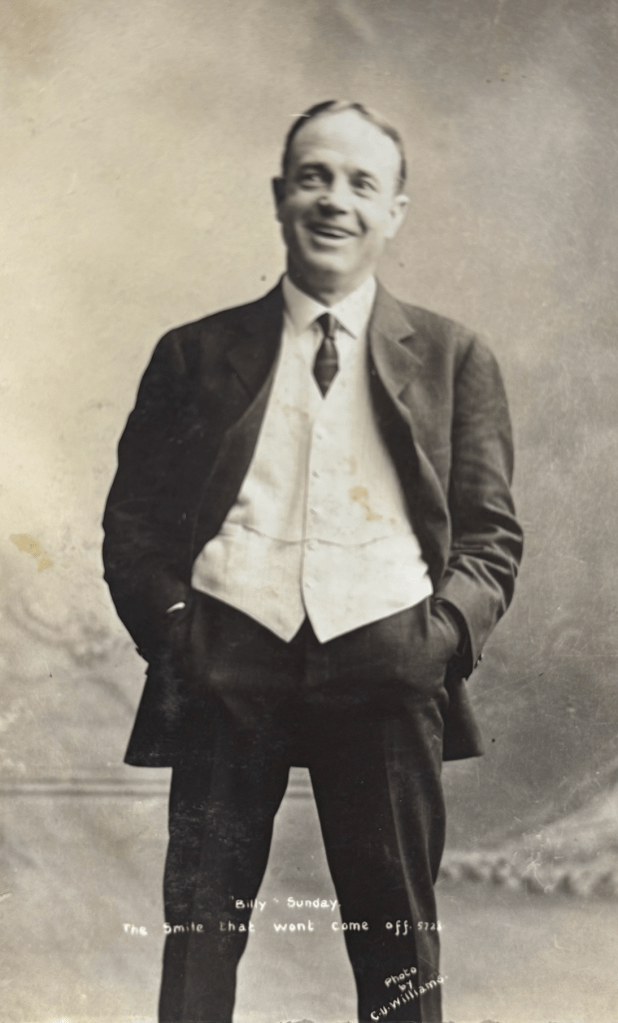

Centre Fielder Billy Sunday made a three-base hit at Farwell Hall last night. There is no other way of expressing the success that accompanied his first appearance in Chicago as an evangelist.

Young men who dodged the boys distributing pamphlets at the door of the hall were confronted with these words blazing in scarlet letters on the big bulletin board:

“William A. Sunday, the base-ball player.”

And about 500 of them who didn’t know much about Billy’s talents as an evangelist, but could remember him galloping to second base with his cap in his hand, went inside. They heard a rattling fifteen minutes’ talk.

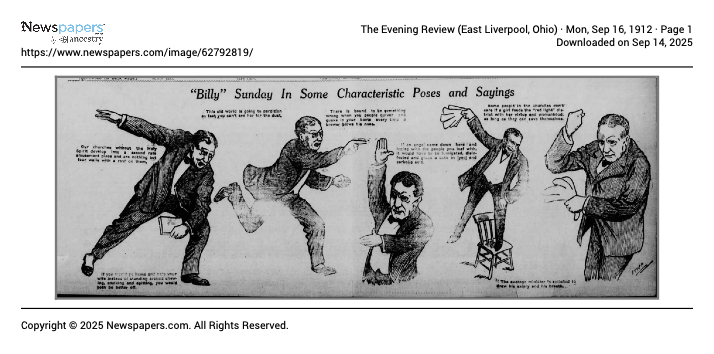

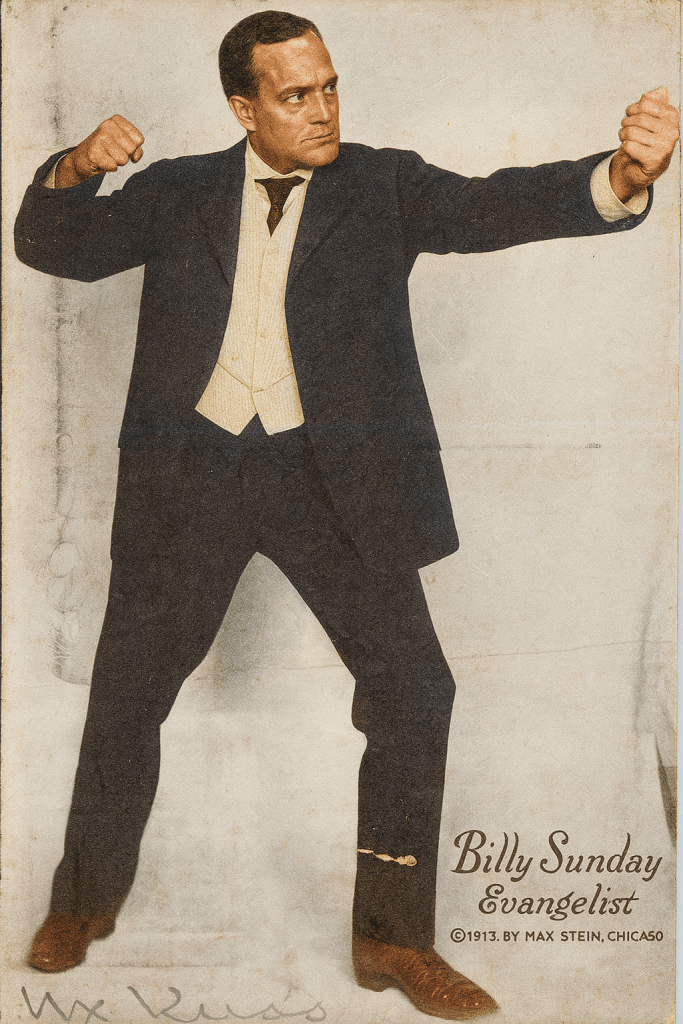

Mr. Sunday, who has grown a red mustache since his marriage, appeared in a becoming black suit and looked a little shy. It was his first public appearance here as an evangelist. In private he had often tried to do quiet work among the ball players, but, after dulling his weapons on the adamantine surface of “Silver” Flint’s moral character, he gave up the task, and for several winters has been preparing for a public trial of his skill in saving souls.

His talk last night was the most successful of the year. He aimed straight at the young men in front of him, giving them the truth in plain, earnest language, and when he finished forty-eight youths raised their hands to show that they had been converted. Sunday looked as pleased as a man who has stolen third.

AT THE BAT.

His talk was from the text: “Is the Young Man Safe?”

“Is he safe?” said Mr. Sunday. “Do you think he is safe, boys – do you think he is safe? I answer no. This is a big city. It is full of temptations. No young man is safe in it without Christ. With Him there is security. Without Him – O! think of the pitfalls and iniquity that drag young men down to sin and death.”

The little ball player walked across the stage with the springing gait of an athlete, and turned suddenly on his audience: “There are a great many questions of vast importance to us as individuals and as a Nation—questions that call for men of keen intellect and for thought—such questions as the tariff and labor. Vast and important as these are, they sink to oblivion when compared to the question of your soul’s future home. Ah! my boy, that is the big question. Christ calls across a chasm of 1,800 years: ‘Son, give me thine heart.’ Today the seat of war is confined to no one nation or battlefield. It rages all over this earth, on the Hudson, on the Mississippi, on the Nile, on the Danube. It is the battle against sin. Ever since Cain slew Abel in the Garden of Eden that battle has been raging, and it will rage so long as the earth stands. What side are you on?

“Think of the thousands that fall in the battle of life, no hope, no home, no heaven. Look at it right, boys. Satan doesn’t want to get a young man who after a while may dispute with him the realm of everlasting meanness. You bet he doesn’t. It is the generous young man, the warm-hearted young man, the ardent young man, the sociable young man who is in danger, my friends. He’s the fellow that Satan behind the bat wants to catch napping. He’s the chap that the Devil in the box wants to pull on with a snake curve. Hold your base. Wait for your ball.”

“WATCH THE ERROR COLUMN.”

Sunday was in earnest. He grew eloquent. “Say to yourself, O my friends, God helping me, I will take my Bible, light for all darkness, balm for all wounds, grand, glorious, the best book you ever owned. If you haven’t got a Bible now, my lads, get one. It will show you the paths of safety and warn you of the danger of the paths of sin: ‘Whoso putteth his trust in the Lord shall be safe.’

“Is there a voice within you saying: ‘What did you do that for? Why did you go there? What did you mean by that?’ Is there a memory in your soul that makes you tremble—is there such a memory, fellows? God only knows all our hearts. He is familiar with the catalogues of our sins. How many hits have you made and where do you stand in the error column?”

Mr. Sunday then led the audience in singing the hymn:

Safe in the arms of Jesus,

Safe from corroding care,

Safe from the world’s temptation,

Sin cannot harm me there.

Forty-eight persons acknowledged the effect of Mr. Sunday’s manly and earnest talk—the best showing made at a Farwell Hall Sunday night service in a year. After the regular meeting an experience meeting was held in the rear of the hall, where Mr. Sunday led in prayer and shook hands with the converts.

“I wish Anson were here,” he said. “What an evangelist the old man would make. No, I’m glad I didn’t take the long trip. I can do more good here bringing souls to Christ. I will play in Pittsburg next summer.”

“Say, how he did line old Satan’s delivery out of the lot,” said a young man at the door. “He hit the ball on the nose every time.”