Post-Bulletin. Tuesday, January 06, 1920: pg 4.

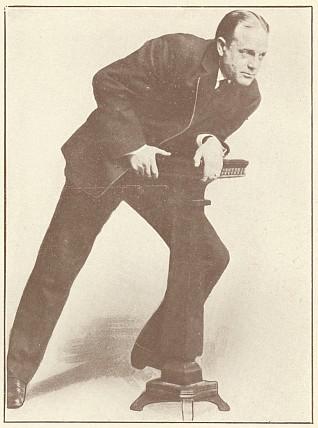

Evangelist Billy Sunday (1862-1935)

Former professional baseball player-turned urban evangelist. Follow this daily blog that chronicles the life and ministry of revivalist preacher William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (1862-1935)

Post-Bulletin. Tuesday, January 06, 1920: pg 4.

by Kraig McNutt

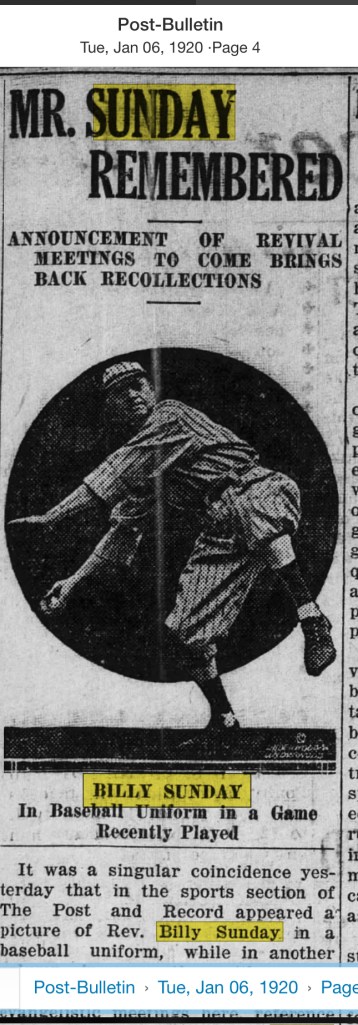

When most people think of revival preachers in American history, names like D.L. Moody, R.A. Torrey, or J. Wilbur Chapman often come to mind. But Billy Sunday was cut from a different cloth. He wasn’t just a preacher—he was a one-man spiritual cyclone, mixing athleticism, theatricality, and gospel fire in a way no one had ever seen before.

So what exactly set Billy Sunday apart from the rest? How did his preaching and ministry differ from his contemporaries? Here’s a snapshot comparison to help you see why Sunday’s voice roared across the American landscape like a thunderclap—and why his influence still echoes today.

| Topic | Billy Sunday | Contemporary Evangelists |

|---|---|---|

| Preaching Style | Fiery, physical, theatrical; used slang and sports metaphors | Moody: Calm and fatherly; Torrey: Intellectual; Chapman: Pastoral |

| Theological Emphasis | Strong focus on personal salvation, substitutionary atonement, and sin | Similar focus, though often with more doctrinal exposition or gentler tone |

| View of Modernism | Vehemently opposed; saw it as a threat to true Christianity | Most were critical, but some (like Fosdick) were sympathetic to modernist ideas |

| Social Issues | Fiercely anti-liquor (Prohibition), anti-gambling, anti-dancing; championed “old-time religion” | Moody: Emphasized charity and urban outreach; others less publicly political |

| Engagement with Politics | Highly political; openly supported Prohibition, patriotic causes, and civic reform | Moody and others were less politically vocal, though supportive of moral reform |

| Use of Media/Publicity | Master of mass media: posters, press coverage, advance men, tabernacles | Chapman and Torrey used some publicity, but far less theatrically or broadly |

| Attitude toward Higher Criticism | Condemned it outright as destructive to faith | Most conservative contemporaries agreed, though some engaged it more thoughtfully |

| View on Women’s Role | Praised godly mothers; Helen Sunday was integral to the ministry, though Billy upheld traditional roles | More varied: some supported women in ministry (e.g., Aimee Semple McPherson) |

| Revival Structure | Mass meetings, community-wide, tabernacles, extended multi-week events | Similar formats, but Sunday’s scale and advance team coordination stood out |

| Legacy Impact | Set the stage for 20th-century mass evangelism (influence on Graham, etc.) | Others laid groundwork (Moody), but Sunday modernized the revival model |

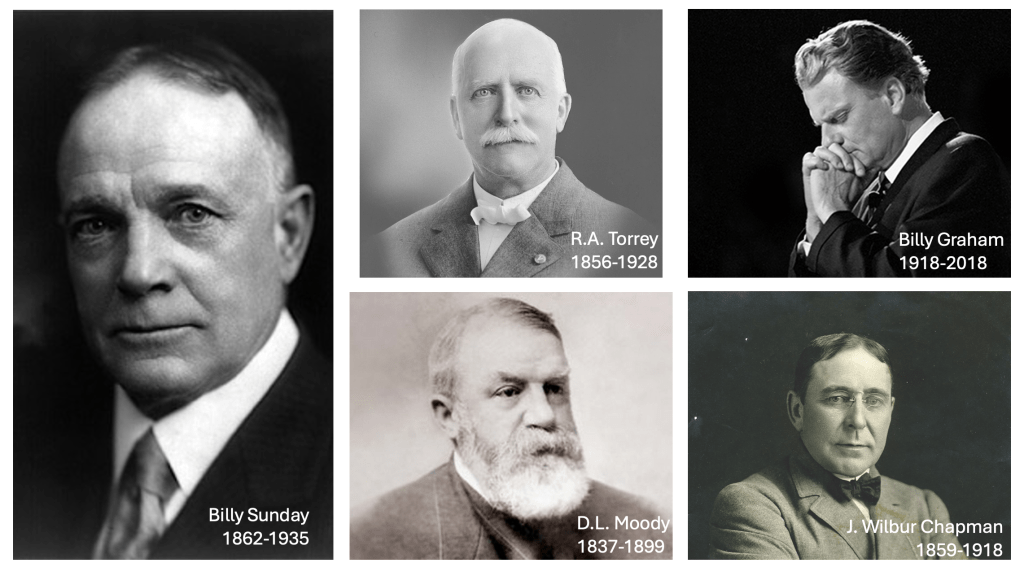

Billy Sunday didn’t fit into a neat category. He was part preacher, part performer, part prophet—and all in for Christ. While others wrote theological treatises or built Bible schools, Sunday pounded his fists on pulpits and dove across stages to bring people to the cross.

His fierce denunciation of sin, especially the sins tearing apart American families—booze, gambling, corruption, moral apathy—connected with the common man. He used theatrical movement, slang, and sports metaphors to reach crowds who might never set foot in a traditional church.

But his legacy wasn’t just showmanship. Billy Sunday built the prototype for what would later become 20th-century crusade evangelism, paving the way for figures like Billy Graham. He made evangelism a national event, not just a church function.

In a world drifting further from spiritual conviction, it’s worth remembering men like Billy Sunday—men who refused to compromise truth, who called a nation to repentance, and who showed that the gospel is worth getting loud about.

Whether you’re a pastor, a historian, or just someone trying to figure out what revival looks like in your day, take a page from Sunday’s playbook: preach it hot, live it loud, and never apologize for loving Jesus.

Commercial. Thu, Jan 13, 1927 ·Page 7

In 1927, renowned evangelist Billy Sunday conducted a six-week revival campaign in Bangor and Brewer, Maine, from May 29 to July 1927.

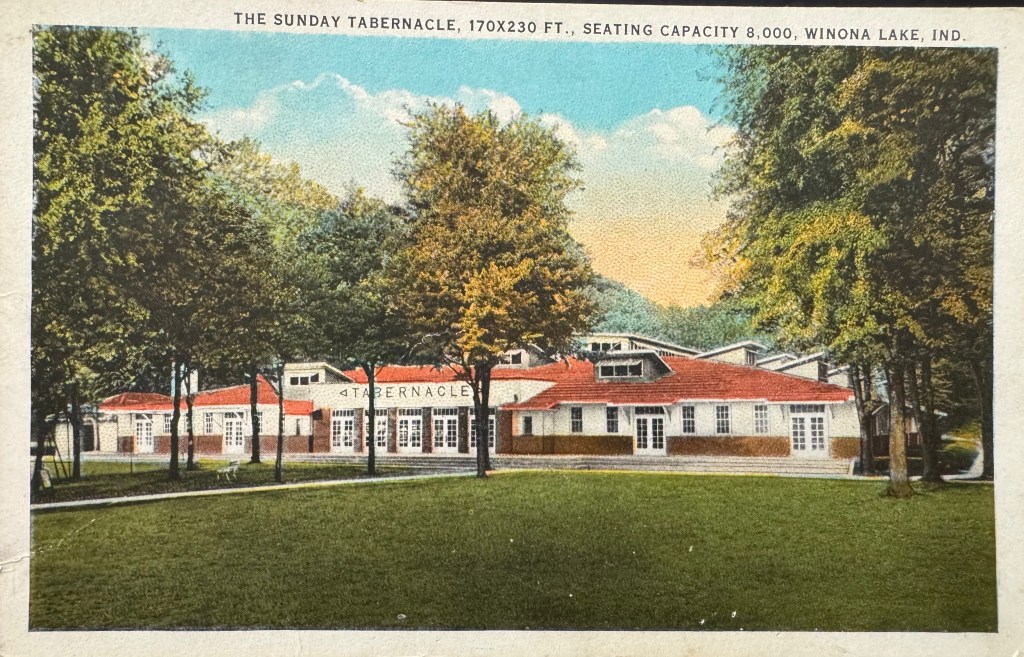

Original postcard with June 1925, Winona Lake postmark on back.

Sent from Harriet Yoder to Hugh Yoder (South Bend, IN)

The Winona Lake Billy Sunday Tabernacle was built in 1921. It was demolished in 1992. At that time it was the last remaining standing Billy Sunday Tabernacle. The Moody Bible Institute (then-called) hosted Bible conferences at the Winona Lake Billy Sunday Tabernacle during it’s last several years of usage. Usually held in July, the experience was hailed as ‘Moody Week.’

The bloghost attended Moody week’s events of 1894-1986, hearing speakers of the likes of Howard Hendricks, Elwood McQuaid, John Walvoord, Warren Weirsbe, Lehman Strauss, Joe Stowell, Marv Rosenthal, George Sweeting, David Jeremiah, and Vance Havner.

By Kraig McNutt

From the moment he arrived in Burlington, Iowa, in November 1905, Rev. William “Billy” Sunday brought with him more than a revival campaign—he brought a storm. For six intense weeks, Sunday preached to thousands daily, confronted sin with his trademark “hammer and tongs” style, and called the city to spiritual awakening.

But the campaign didn’t just stir souls. It nearly cost him his life.

Sunday’s campaign in Burlington ran from November 9 to December 17, 1905. In that span, he preached to crowds of 6,000 to 10,000 in a massive wooden tabernacle built for the occasion. The energy was electric. At one point, over 1,279 converts had been counted, and by the end of the campaign, the total reached 2,484.

The Muscatine Journal described Sunday’s preaching as if “swaying a storm-beaten ocean.” In a men’s meeting alone, 112 responded to the call, with many more turned away due to overcrowding.

But Sunday’s sermons weren’t just altar calls—they were cultural critiques. He lambasted spiritual apathy, criticized parental neglect, and took direct aim at profanity, indifference, and moral complacency. In one memorable line, he warned:

“You say, ‘It is nobody’s business what I do.’ But hear me—it is everybody’s business what everybody does.”

His sermons were equal parts gospel and social conscience.

Not everyone was thrilled. A Cedar Rapids Gazette editorial warned that while Sunday was sincere, his tone could be offensive and even vulgar. Some churchgoers felt he used “language of the gutter” and painted humanity as far too depraved. They admired his passion but questioned his method:

“Offensiveness and vulgarity may emanate from the pulpit as well as from any other source… but ‘Billy’ Sunday is sincere, and sincerity is a virtue that is not to be despised.”

It was this very sincerity—his relentless, full-throttle commitment—that finally broke him.

On Monday, December 18, 1905, as Sunday prepared to preach to yet another crowd of 4,000, he suddenly collapsed on stage, fainting in front of the shocked audience. Reports soon circulated that his life was in danger, and that weeks of nonstop preaching had led to total physical and nervous exhaustion.

The Dixon Evening Telegraph wrote:

“He had been preaching steadily day and night for months and during the preceding week had not slept.”

While Sunday recovered and eventually continued his national ministry, the Burlington collapse marked a critical moment—a reminder that even spiritual giants are still human.

Despite the toll on Sunday’s health, the Burlington campaign left deep footprints in the city. By the time the tabernacle closed:

According to The Grand Rapids Press, the final night saw 7,000 people crammed inside, with 5,000 more unable to get in. It was one of the most dramatic and consequential campaigns of Sunday’s early career.

The Burlington campaign reveals the paradox of Billy Sunday’s revivalism:

Still, Sunday “played ball” in the pulpit the way he had on the baseball field: heart first, full speed, no reserve.

And in December 1905, Burlington, Iowa, witnessed both the brilliance—and the breaking—of a man determined to bring America back to God.

Billy Sunday conducted his revival campaign in Burlington, Iowa, from November 9 to December 17, 1905. He saw 2,484 conversions and generated $4,000 in collections. A newspaper article tells how he fell ill and his very life was deemed threatened during the Burlington campaign.

Reported That Evangelist Sunday Was Taken Ill During Meetings.

It is reported that Rev. “Billy” Sunday, who has hundreds of friends in Dixon, has broken down from overwork and nervous strain and is dangerously sick at Burlington, Iowa. Friends here have heard nothing of this but the following item is published in an exchange:

“Billy” Sunday, the famous baseball evangelist, broke down at a revival near Burlington, Iowa, Monday, and his death is feared. Sunday started to preach to a crowd of 4,000 people when he toppled over on the platform in a dead faint. He had been preaching steadily day and night for months and during the preceding week had not slept.”

REV. “BILLY” SUNDAY.

Burlington is now in the throes of a religious awakening, engineered by that eminent and popular ex-baseball player who now is known as Rev. William A. Sunday, but whose numerous friends still love to call “Billy” Sunday. Sunday has been preaching the old gospel in his own inimitable style for several years, and has drawn to him the friendships of a great many people of all denominations, while he has also offended many good people by his “hammer and tongs” style of argument. He has also many friends among the people outside of all churches, for there is one thing of which “Billy” Sunday cannot be justly accused, and that is insincerity. He preaches just like he played ball—puts his whole heart into the work; in other words, he “plays ball” in his present profession. That he has done and is doing great good cannot be successfully denied, and Burlington will probably be better, for a time at least, for his coming; but he has many friends who do not believe it is necessary to use the language of the gutter in condemning evil, nor that everybody is quite as bad as Mr. Sunday would sometimes have his hearers believe.

Offensiveness and vulgarity may emanate from the pulpit as well as from any other source. And it is barely possible that a religious cathartic may not prove as effective in the long run as a less drastic and more constructive remedy.

Again, those who labor just as hard, year in and year out, and just as faithfully, in the noble calling, at a salary generally less per annum than Mr. Sunday receives in a fortnight, may be doing a more permanent work. But “Billy” Sunday is sincere, and sincerity is a virtue that is not to be despised.

GREAT REVIVAL.

Evangelist “Billy” Sunday Stirs Up Burlington—Large Crowds.

Burlington, Ia., Nov. 28—The revival services conducted by Rev. William A. Sunday have already grown to be a remarkable thing for Burlington. They have been going on for two weeks, and the evangelist is now speaking to an average of 6,000 people daily. Sunday afternoon he held his first men’s meeting and was greeted by fully 6,000 men, old and young. He swayed this remarkable audience for an hour and a half like a storm beaten ocean and at the close 112 men responded to the call for converts, and it is estimated that 50 were turned away because of the crush in front of the evangelist. Including this number there have been a total of 602 converts since last Thursday night.

SOME “BILLY’ SUNDAYISMS.

From Burlington papers: The indifference of many in the church is keeping back the kingdom of God.

Some of you are constantly breathing out in doing good to others, but do no breathing in; seldom or never give yourselves any time with God.

If you have done your neighbor in jury, go to him and confess it, and ask his forgiveness.

The greatest barrier to the advancement of God’s Kingdom to-day is the indifference and apathy of so many of our church members.

No wonder so many of our children go to the bad; they get no guidance, no inspiration, no help for good in the home.

There are hundreds here to-night who are convinced that Jesus Christ is the son of God, but have not back- bone enough to come down the aisle and confess it.

The historical Jesus? You may repudiate him as the son of God, but you still have the historical Jesus, and you could no more write the history of the world and leave Jesus out than you could write the history of this country and leave out George Washington.

Profanity damns and curses any man who indulges in it.

What would the world be were there no restraining influence? You say “it is nobody’s business what I do.” Bu’ hear me, it is everybody’s business what everybody does.

There are certain men who scoff at religion and at preachers, but when they come face to face with death and the fearful consequences of their dis- solute lives they begin to fear and tremble.

Ten thousand people sought to hear “Billy” Sunday preach at Burlington last Sunday, 6,000 succeeding. Converts in his revival services in that city to date number 1,279.

Closed by “Billy” Sunday.

Burlington, Ia., Dec. 20.—The wave of reform in Burlington, growing out of William A. Sunday’s revival meetings, resulted in the formation of the Civic Reform league of 150 members, and the issuance last night by Mayor Caster of an order closing all saloons on Sunday.

2,500 Converts

Secured by Rev. Billy Sunday in Burlington

Burlington, Ia., Dec. 19.—The Rev. William A. Sunday has closed his series of evangelistic meetings here. There were 7,000 people packed into the tabernacle, with at least 5,000 outside unable to get in, last night. The results of the meetings are 2,500 converts. The people of Burlington have given him a free-will offering of over $4,000.

Here’s a blog-ready narrative reflecting on the 1904–1905 campaign data from Billy Sunday’s early revivals:

By Kraig McNutt

Before Billy Sunday became a national sensation—packing tabernacles in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh—he cut his evangelistic teeth in smaller Midwestern towns. The data from his 1904–1905 revival campaigns offers a fascinating glimpse into the early momentum of a man who would become America’s most celebrated evangelist of the early 20th century.

Here’s what the numbers reveal.

Many of the towns on Sunday’s early itinerary were small agricultural or industrial communities scattered across Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, and Colorado. Places like Exira, Iowa and Audubon, Iowa boasted modest populations—yet hundreds came forward to respond to Sunday’s message.

These numbers are especially impressive when viewed through the lens of population density. In many cases, Sunday was reaching 10–20% or more of the town’s residents. His message wasn’t simply heard—it reshaped the spiritual landscape of entire communities.

While conversion data was consistently recorded, collections (monetary offerings) were only occasionally noted:

These figures indicate that even in smaller towns, there was strong financial support for revival efforts. The money likely covered the costs of tabernacle construction, music, printed materials, and Sunday’s own ministry team.

These generous gifts also reflect the deep gratitude communities felt for the spiritual impact they experienced.

Across 22 cities recorded between 1904 and 1905, Sunday saw tens of thousands make public professions of faith. The median number of conversions hovers around 900–1,000 per town. For a relatively unknown evangelist in his early 40s, this marks a period of accelerating credibility and growing influence.

It was this consistency—town after town, soul after soul—that built the foundation for Billy Sunday’s national platform just a few years later.

It’s no accident that Sunday’s early years focused on Iowa, Illinois, and Minnesota—regions that mirrored his own upbringing and values. These were towns where the church was central, alcohol was a public enemy, and personal salvation was not just a religious idea, but a community matter.

Sunday’s fiery oratory, moral clarity, and theatrical flair found fertile ground in these heartland soils.

The revival fires Billy Sunday lit in places like Bedford, Harlan, and Canon City were more than regional events—they were launchpads. These early campaigns showed that revival could still grip a town, change hearts, and reorder lives.

In 1904 and 1905, he wasn’t yet preaching to hundreds of thousands—but he was proving that he could.

And history shows—he would.

Enjoying this kind of historical insight? Subscribe to the blog or check out more posts at EvangelistBillySunday.com

Source: The Spectacular Career, p. 126.

| City | Conversions | Collections |

| Marshall, Minn. | 600 | |

| Sterling, Ill. | 1678 | |

| Rockford, Ill. | 1000 | |

| Elgin, Ill. | 800 | |

| Carthage, Ill. | 650 | |

| Pontiac, Ill. | 1100 | |

| Jefferson, Iowa | 900 | |

| Bedford, Iowa | 600 | |

| Seymour, Iowa | 600 | |

| Centerville, Iowa | 900 | 1500.0 |

| Corydon, Iowa | 500 | |

| Audubon, Iowa | 500 | |

| Atlantic, Iowa | 600 | |

| Harlan, Iowa | 400 | |

| Exira, Iowa | 400 | |

| Keokuk, Iowa | 1000 | 2200.0 |

| Redwood Falls, Minn. | 600 | |

| Mason City, Iowa | 1000 | |

| Dixon, Ill. | 1875 | 2000.0 |

| Canon City, Colo. | 950 | |

| Macomb, Ill. | 1880 | 3100.0 |

| Canton, Ill. | 1120 |