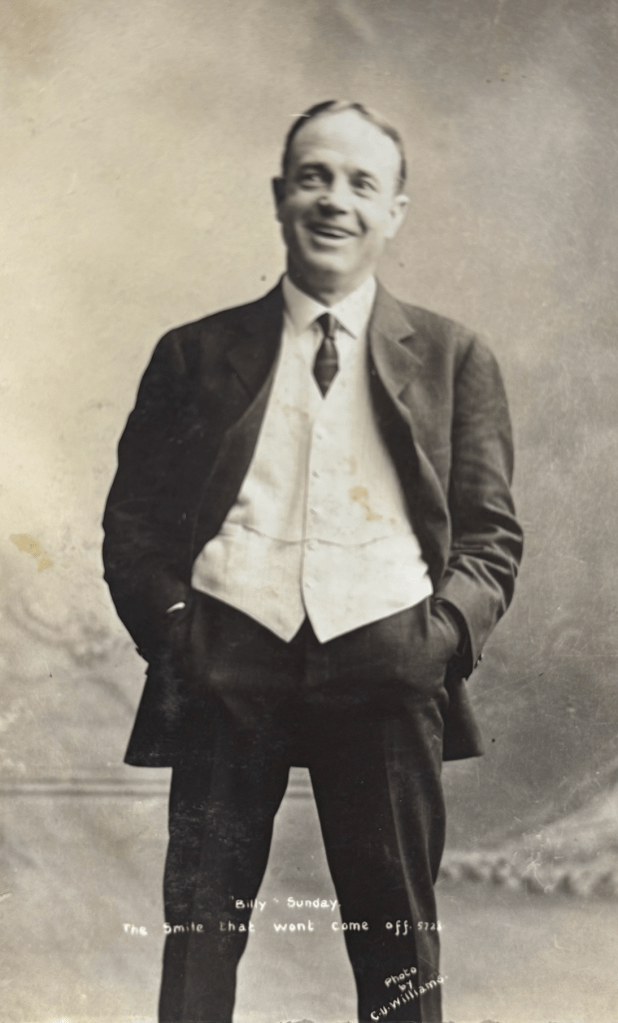

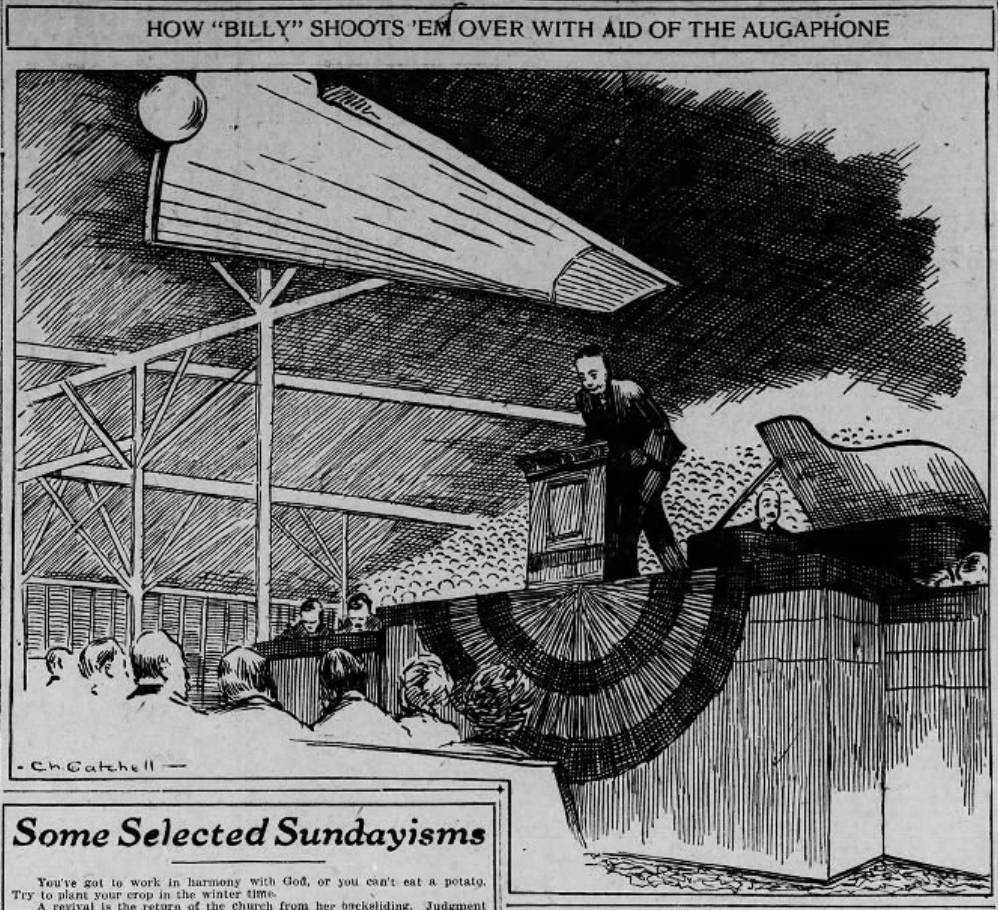

As published in the The Akron Beacon Journal. Sat, Jun 18, 1910 ·Page 3

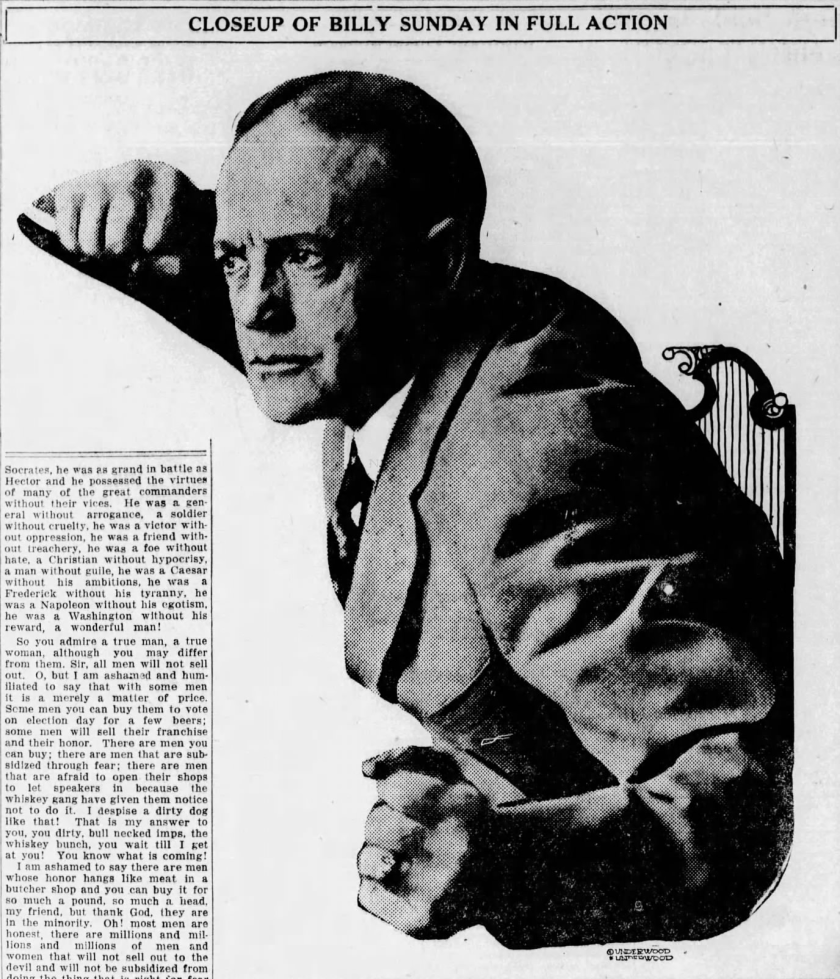

Attorney W. S. Anderson of Youngstown, who defended Bert Petty, is a staunch supporter of “Billy” Sunday, the celebrated evangelist. He was one of Sunday’s many converts in Youngstown. Sunday spent six weeks in Youngstown this spring and Mr. Anderson says that the effect upon Youngstown was great and it has been lasting also.

“When I first went to hear him I was disgusted,” he said, “but I went several times more just out of curiosity and I grew to be a great admirer of his work. The first two weeks he spent in Youngstown he used a great deal of slang. This drew the crowds and when he had them coming he got down to work and his work was wonderful.”

Mr. Anderson says that all classes of people have been effected by Sunday’s work. “The lawyers are a pretty hard class of men to reach with religious services but Sunday did it. One night in his prayer he said, ‘Help the lawyers because we know they are a tough bunch.’ They were too, but many became followers of the evangelist.

“The work of Sunday can not be judged only by the number who came forward. It is the influence on all the people and their relations with one another.”

Mr. Anderson says Akron should get Billy Sunday here. “It will do the town a lot of good,” he said.