When the Tent Met the Tabernacle: How Chautauqua Shaped Billy Sunday’s Evangelism

In the annals of American religious and cultural life, few figures loom as large—or as loud—as Billy Sunday. Baseball player turned fiery evangelist, Sunday crisscrossed the country in the early 20th century, preaching repentance with the speed of a sprinter and the flair of a vaudevillian. But while his legacy is often associated with revivalism, the DNA of another cultural institution runs unmistakably through his ministry: the Chautauqua movement.

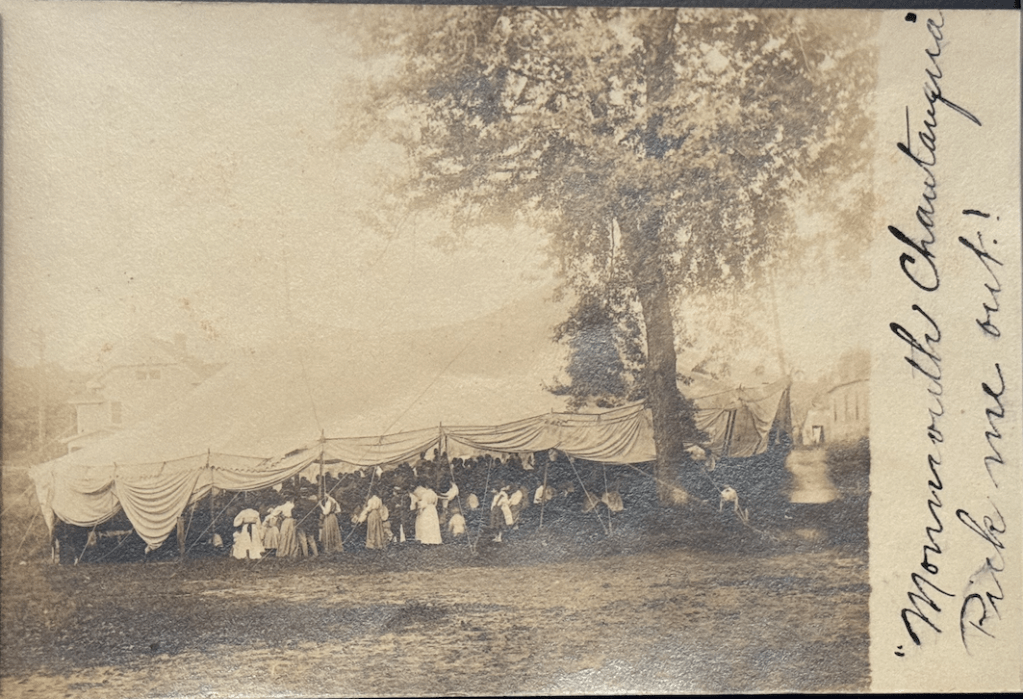

Author’s collection.

At first glance, Chautauqua and revivalism might seem like distant cousins. One promoted moral uplift through lectures, music, and education. The other sought soul transformation through emotional preaching, altar calls, and fervent prayer. But in the figure of Billy Sunday, these two worlds converged. His campaigns became a kind of hybrid phenomenon: part Chautauqua, part revival, and fully American.

The Chautauqua Tradition: A Traveling Feast of Ideas and Morals

Founded in 1874 on the shores of Chautauqua Lake, New York, by Methodist minister John H. Vincent and inventor Lewis Miller, the original Chautauqua Assembly was conceived as a summer Bible training camp for Sunday School teachers. But it quickly evolved into something broader: a nationwide movement combining education, religion, entertainment, and civic virtue.

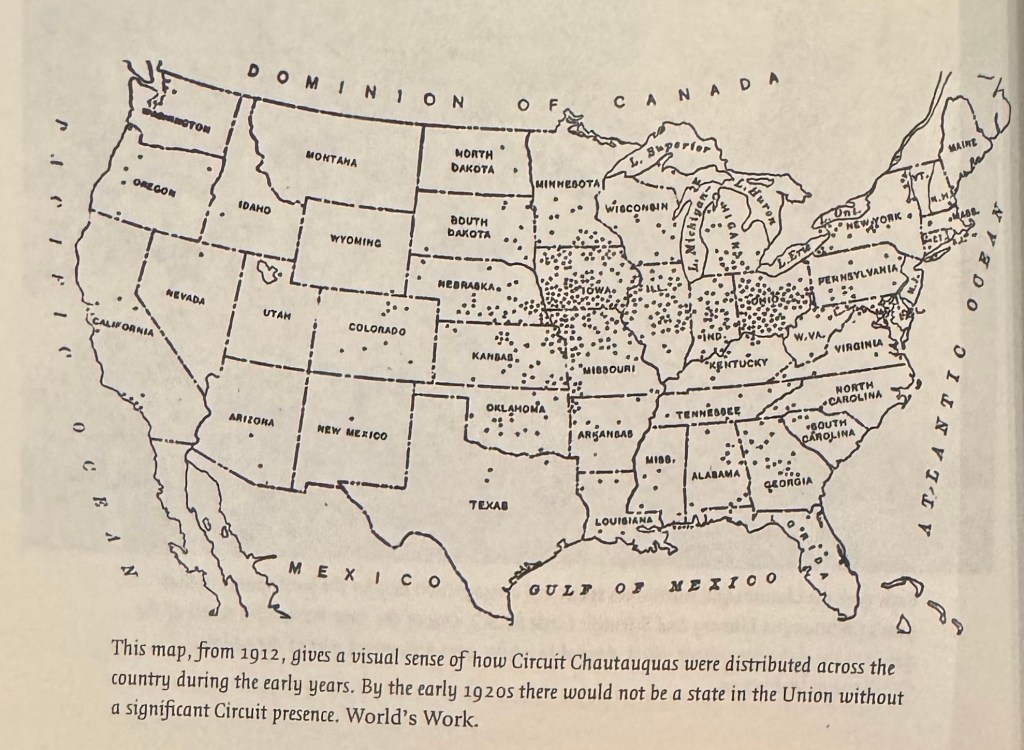

Chautauquas—especially circuit Chautauquas—toured rural America with tents, stages, and full programming that brought lectures, concerts, and clean entertainment to small-town audiences. They celebrated middle-class Protestant values, offering inspiration in digestible, family-friendly form.

Enter Billy Sunday

By the late 1890s, Billy Sunday had left baseball behind and was learning the ropes of itinerant evangelism. His early mentors, J. Wilbur Chapman and R.A. Torrey, both had connections to the broader Chautauqua scene. Torrey especially was a regular Chautauqua speaker, bringing theology to the people in accessible form.

Sunday’s own gifts—storytelling, humor, physical theatrics, and moral fervor—were tailor-made for the Chautauqua stage. Though he would later distinguish himself through large-scale revivals and sawdust trails, his early career intersected directly with the Chautauqua movement.

Vawter’s Influence on Sunday

One of the pivotal figures behind Sunday’s deeper involvement with the Chautauqua model was Keith Vawter, the mastermind of the circuit Chautauqua system. According to scholar John E. Tapia, Vawter recognized Sunday’s potential to reach mass audiences and personally encouraged him to join the Redpath Chautauqua circuit. Vawter believed Sunday’s electrifying delivery, athletic stage presence, and moral seriousness would resonate strongly with Chautauqua crowds. Sunday accepted Vawter’s invitation in 1910, a move that proved strategic. Through the Chautauqua platform, Sunday expanded his audience, sharpened his performance style, and laid the groundwork for the national revival campaigns that would follow.

Evidence of Sunday at Chautauquas

Thanks to primary sources and local records, we now know that Billy Sunday didn’t just resemble a Chautauqua speaker—he was one:

Clarinda, Iowa (August 6, 1908) – A postcard written by a local resident records hearing a “Billy Sunday lecture” at the Clarinda Chautauqua. Not a sermon—a lecture. The terminology matters. It shows that Sunday knew how to tailor his message to fit the expectations of a Chautauqua crowd: moral, inspiring, and educational.

Glenwood Park Chautauqua, New Albany, Indiana (c. 1910) – Sunday spoke at this established Chautauqua venue, likely during his period of growing regional fame. He was still accessible to small- to mid-sized communities, many of whom relied on Chautauqua programs to deliver cultural and religious content. Citation source that documents this: New Albany Evening Tribune, July 28, 1911.

Merom Bluff, Indiana (1905–1936 window) – A historical marker affirms that Billy Sunday was among the Chautauqua speakers at this prominent Indiana site, which also hosted Union Christian College and later became a Christian conference center.

Style and Structure: Chautauqua Meets Revival

Billy Sunday’s campaigns began to take on the structure and tone of a Chautauqua assembly:

- Large tent gatherings or temporary tabernacles, much like Chautauqua’s traveling canvas venues.

- Multi-day programs with scheduled content: music, oratory, public testimonials.

- Musical programs and choirs, often with well-known gospel singers.

- Printed programs and media promotion, echoing Chautauqua’s organized outreach and civic coordination.

Yet Sunday brought something extra—a sense of urgency that Chautauquas, with their genteel tone, typically lacked. He fused the moral inspiration of Chautauqua with the soul-piercing call of revivalism. His tabernacles weren’t just tents for listening; they were arenas for decision.

Cultural Cross-Pollination

Chautauquas were formative in shaping expectations for public religious discourse. They taught small-town America that religion could be engaging, moral talk could be entertaining, and spiritual renewal didn’t have to be confined to Sunday morning.

Billy Sunday absorbed this atmosphere. And then he supercharged it.

- He was more animated than the average Chautauqua speaker.

- More confrontational than the typical reformer.

- But he drew from the same well: public performance for private transformation.

Legacy: The Best of Both Worlds

By the time Sunday’s revivals were drawing tens of thousands in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, they had become national spectacles—but their format still bore the fingerprints of Chautauqua:

- A well-run operation.

- A mixture of culture, faith, and public engagement.

- A populist appeal that transcended denominations and drew in families, skeptics, and civic leaders alike.

His campaigns offered what Chautauqua promised—but with an eternal decision point at the center.

Conclusion: When the Tent Met the Tabernacle

To understand Billy Sunday is to recognize that he wasn’t merely a revivalist in the tradition of Charles Finney or Dwight Moody. He was also a cultural performer in the lineage of Chautauqua. His ministry represents a moment when two great American traditions—moral uplift through public culture and urgent gospel proclamation—merged under one tent.

Billy Sunday didn’t just inherit the Chautauqua model; he transformed it. In doing so, he left behind not only converts, but a new standard for religious communication in the public square: part educator, part entertainer, part prophet.