Chicago Tribune. Mon, May 20, 1918 ·Page 1

49,165 SOULS AND $56,000, BILLY’S SCORE

Great Crowd Hears Revivalist Close Campaign.

Trail hitters (total) ………… 49,165

Attendance at tabernacle and meetings led by members of the Sunday party ………… 1,200,000

Money raised for current expenses ………… $135,000

Money raised for free will offering to Billy Sunday, which he will give in its entirety to the Pacific Garden mission ………… $56,000

Number of churches co-operating ………… 424

Length of campaign (including 11 Sundays) ………… 10 weeks

BY THE REV. W. B. NORTON.

Billy Sunday has prepared his own epitaph, which he says he wants chiseled on his tombstone when he shall be laid away in Forest Home cemetery, where, he says, he expects his body to rest. It is this:

“I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith: Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, shall give me at that day.”

Last night Billy announced the end of his revival campaign here by saying:

“I’ve done my duty. Like a physician after he hands the new baby over to the mother and the nurse, takes his departure, so I commit these new converts to the churches and I go on my way to other fields.”

A Strenuous Finish.

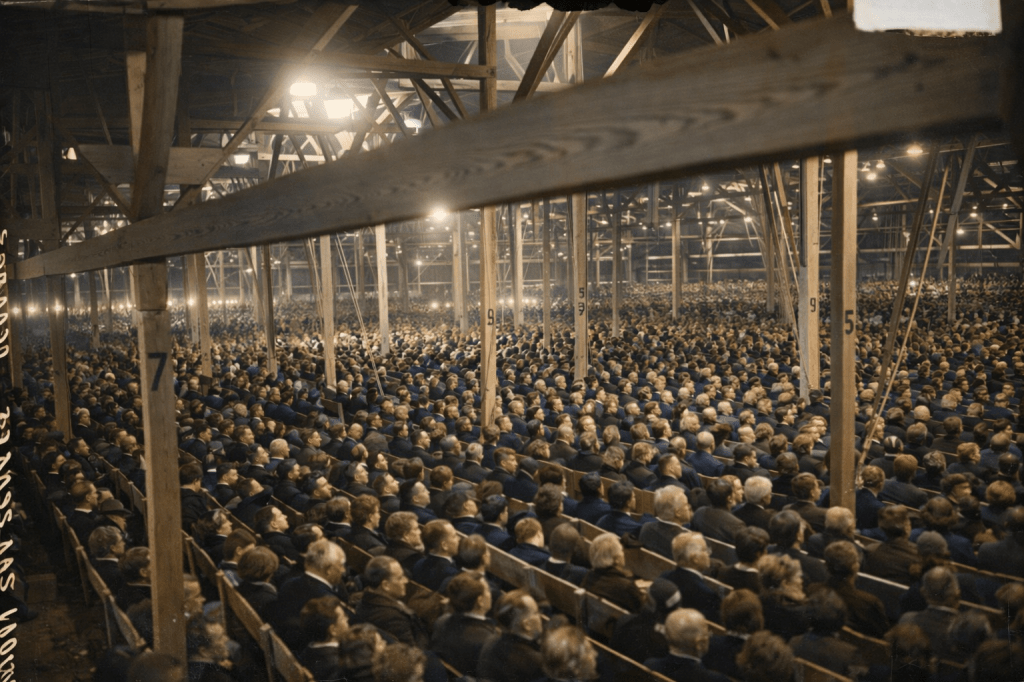

For the first time since Billy began preaching in the tabernacle at Chicago avenue and the lake ten weeks ago, he pulled off both coat and collar and went at his task as in the old baseball days. It was his final sermon and he put into it all the power and feeling he could command.

The rain beat heavily on the roof, and occasionally an umbrella began to rise, but was quickly put down again, so as not to obstruct the view of others. Finally all of the roof windows were closed and the doors opened. At least 13,000 were present, many of them standing. A considerable number were in the seats at 5 o’clock with knitting or papers in hands, determined to have a seat for the final service, no matter how large the crowd.

Appeals for the free will offering for Billy, which is to go to the Pacific Garden mission, were made by George W. Dixon, chairman of the committee on the offering; W. A. Peterson, chairman of the finance committee; the Rev. John Timothy Stone, and Mel Trotter, superintendent of the Pacific Garden mission.

Chicago Tribune. Mon, May 20, 1918 ·Page 4

Sunday Is Pleased.

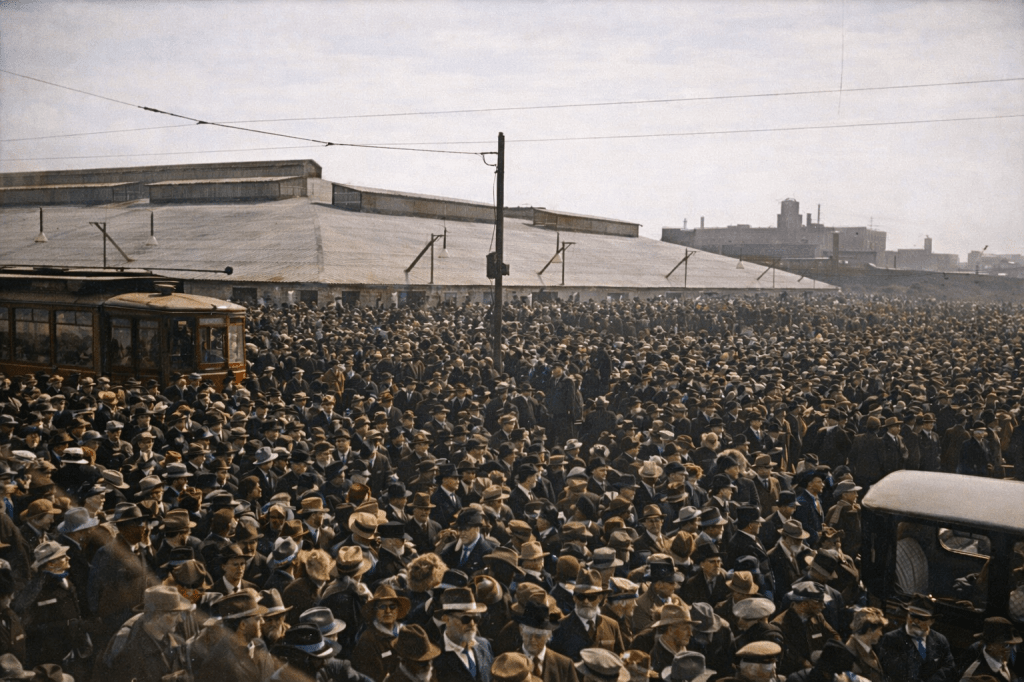

“I consider the most remarkable feature of the meetings has been the evident hunger of the people to hear the gospel, their eagerness of attention, and the steadiness with which they have come,” Mr. Sunday said yesterday. “Every time the invitation has been given there has been a steady stream of hitters, not as I have seen it elsewhere, many coming at one meeting and almost no one the next time. I feel that it has been a remarkable meeting.”

Chicago Tribune. Tue, Jun 25, 1918 ·Page 3

The building (at Chicago Avenue and the lake) is the largest tabernacle ever built for the use of Mr. Sunday and was fourteen feet longer than the next largest one built in New York. It accommodated an audience of 16,000 when the vestibule was filled, as was done on several occasions during the revival campaign.

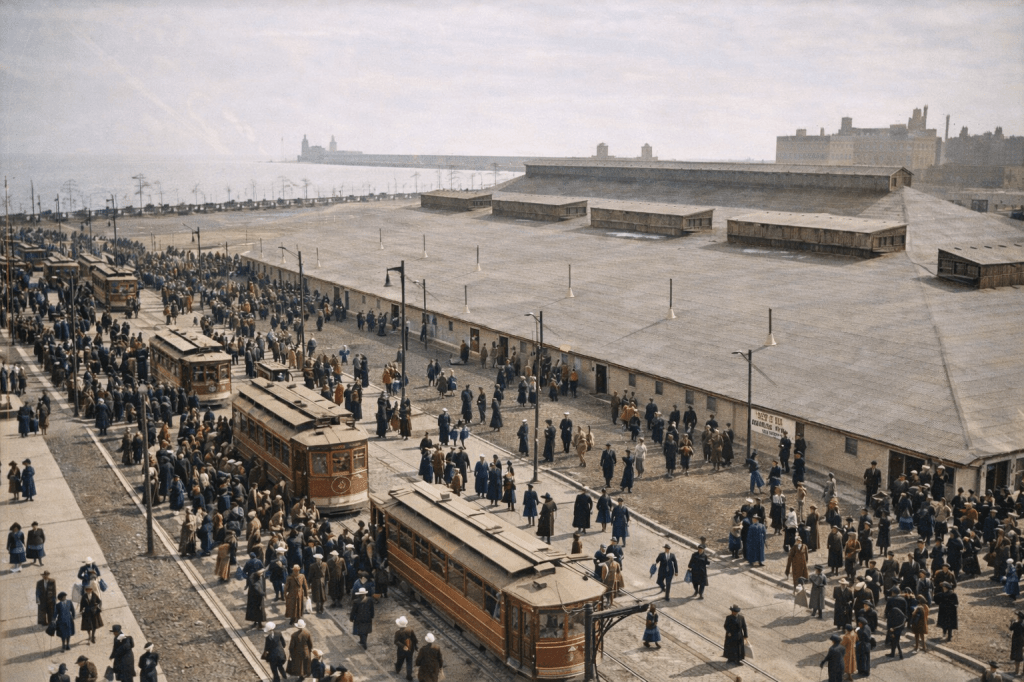

More images of the Chicago 1918 campaign.