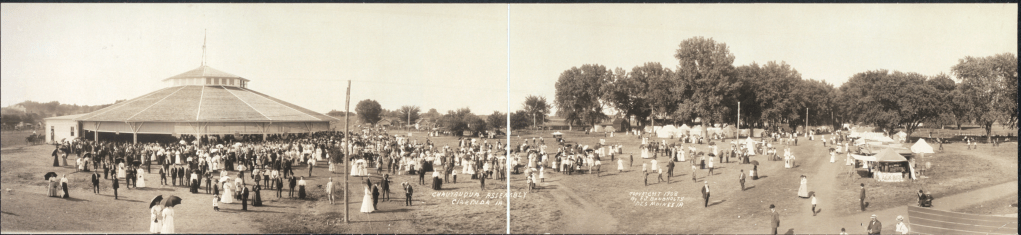

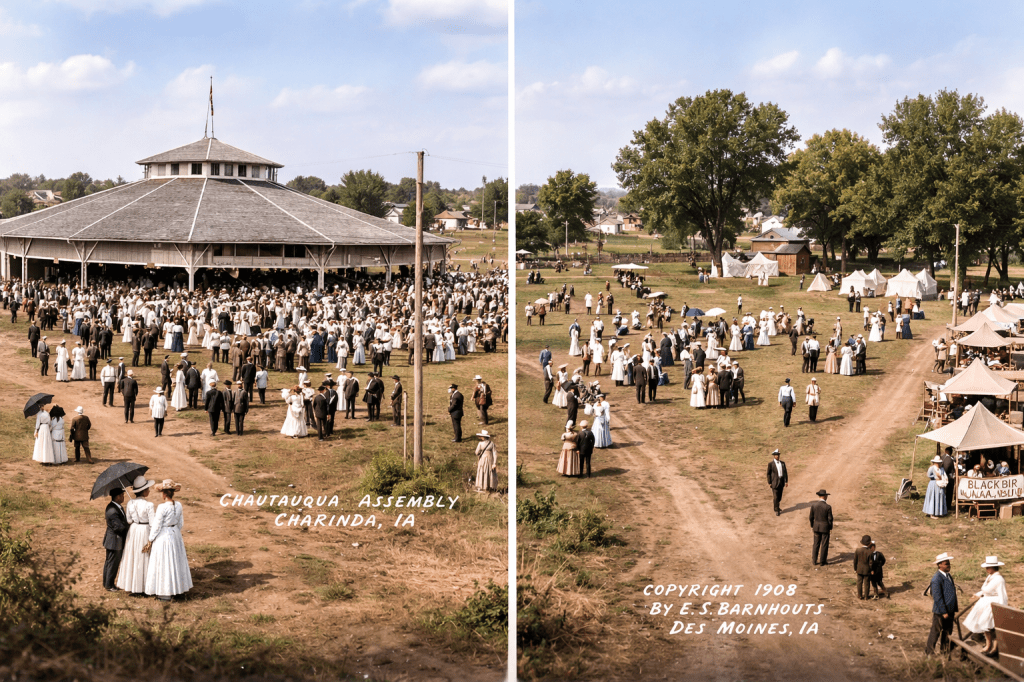

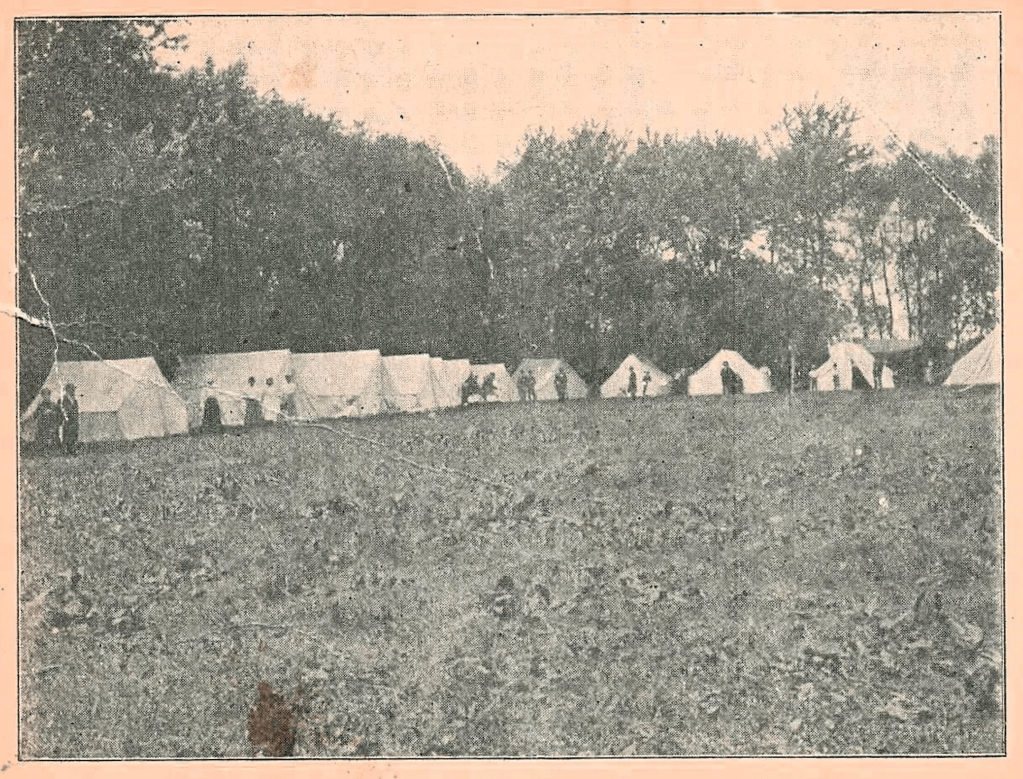

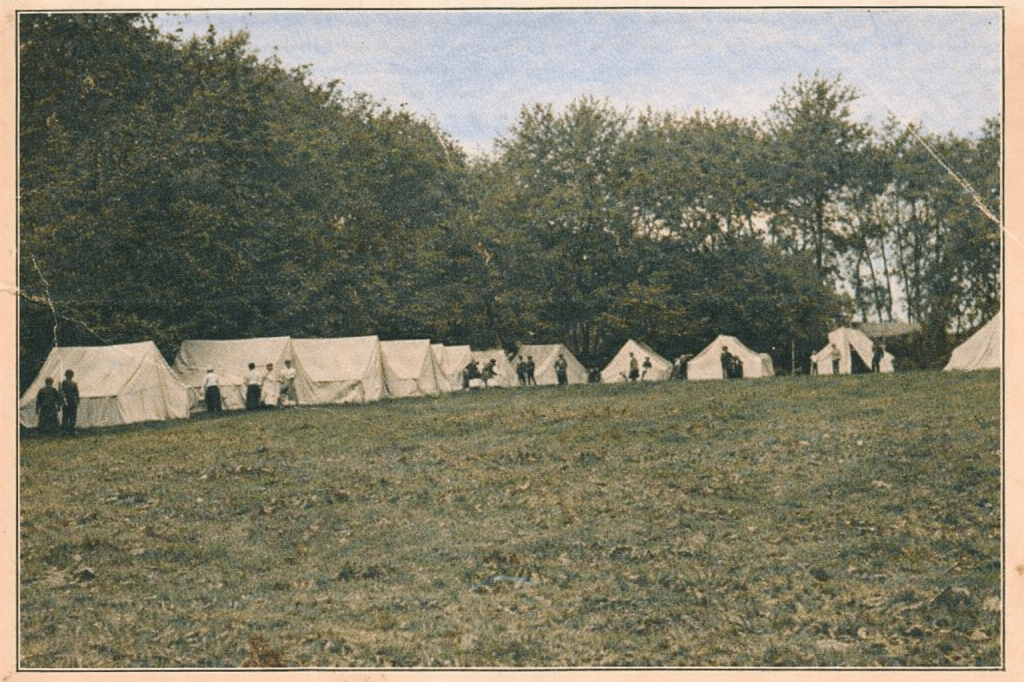

Billy Sunday spoke at the Clarinda, Iowa Chautauqua on August 6, 1908.

Colorized

Evangelist Billy Sunday (1862-1935)

Former professional baseball player-turned urban evangelist. Follow this daily blog that chronicles the life and ministry of revivalist preacher William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (1862-1935)

Billy Sunday spoke at the Clarinda, Iowa Chautauqua on August 6, 1908.

Colorized

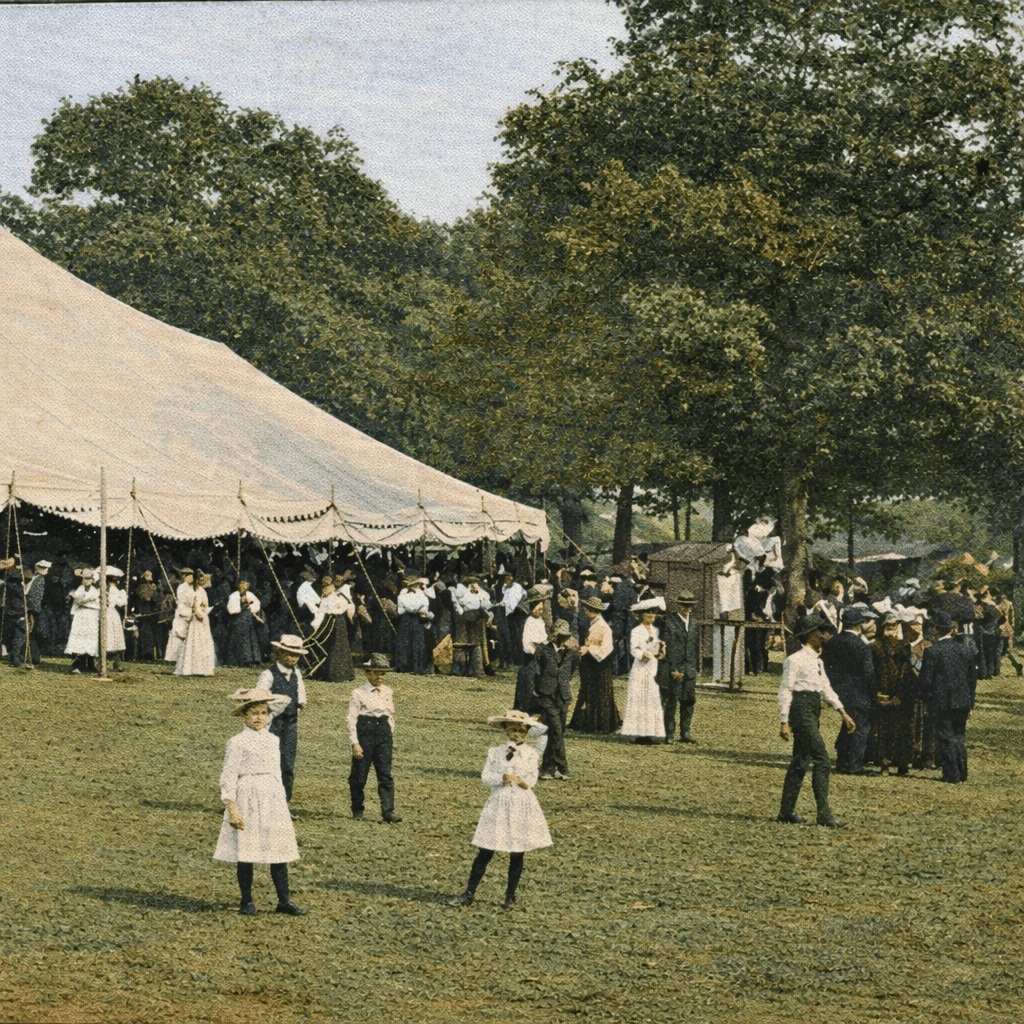

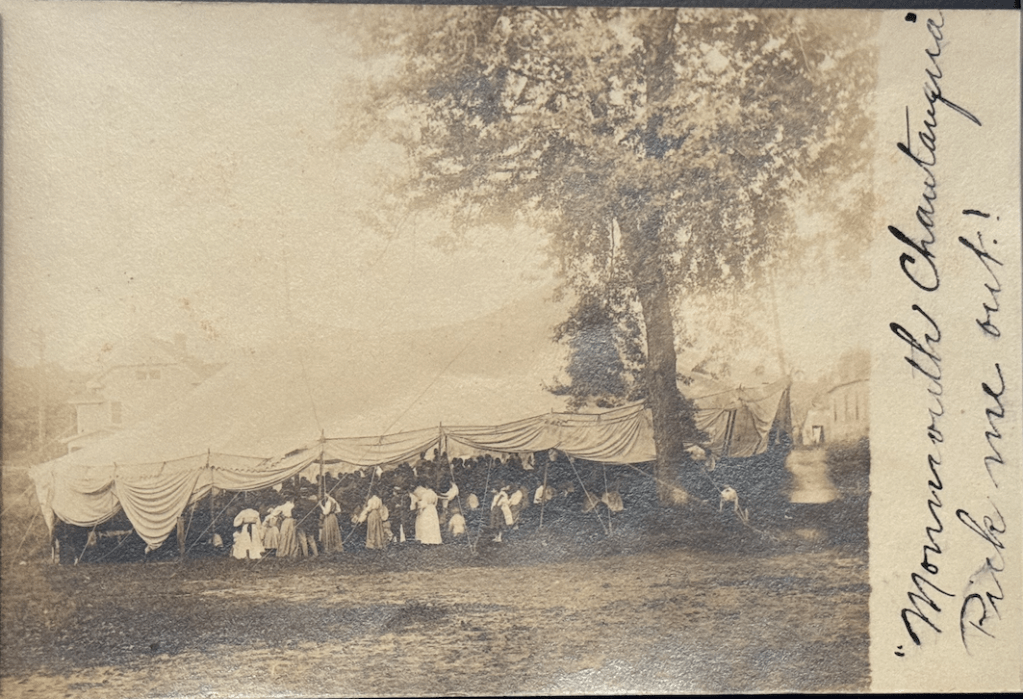

c. early 1900s. Possibly a chautauqua event.

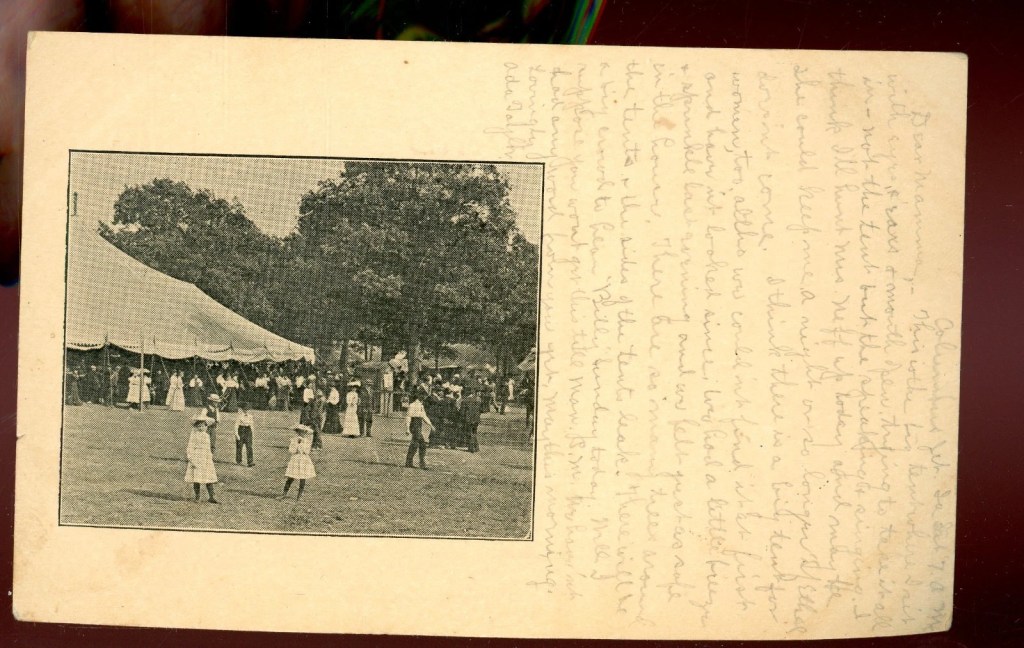

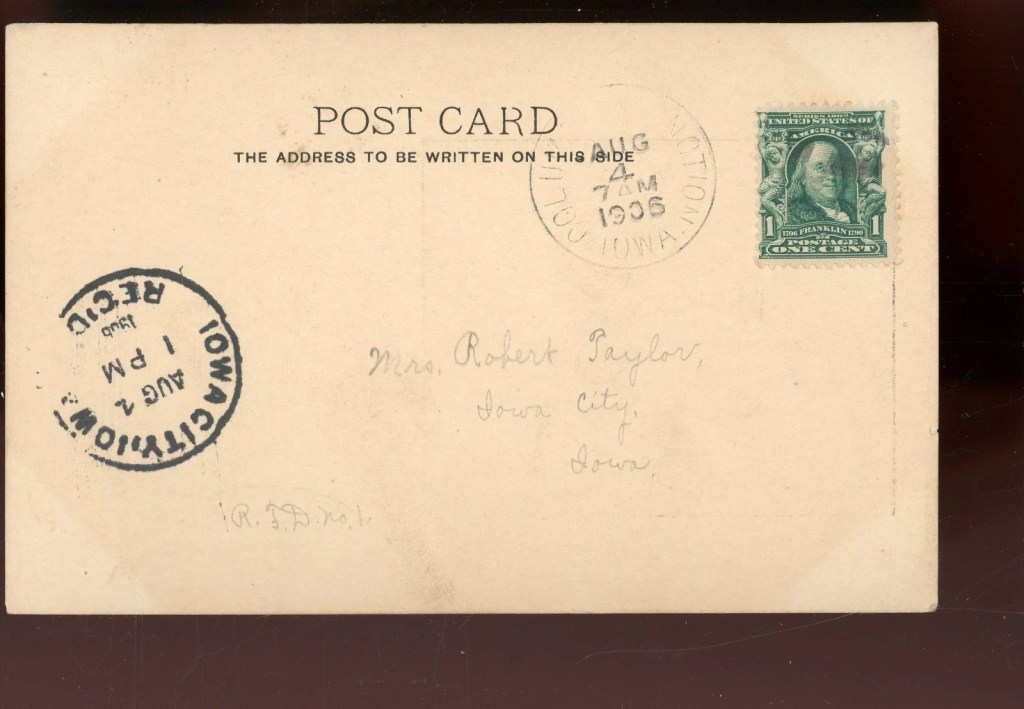

Postcard verifies Billy spoke “today” in Columbus Junction, Iowa (Chautauqua)

Hannibal, Missouri paper

“BILLY” SUNDAY

Revivalist and Chautauqua Headliner

Thomas E. Green, well known to Chautauqua audiences published in the June 1910 issue of Hampton’s Magazine, an article on “Revivals and Revivalists.” The whole article is full of interest. Chautauqua Committees who have booked Billy Sunday will do well to secure it, as it furnishes splendid material for publicity. He quotes the following estimates of Sunday’s work in places where he has held meetings: The leading pastor in the converted city, a man of ripe judgment, said: “I looked forward to this thing with a great deal of anxiety. When the evangelist came he quite captured me. He is unique. There is only one of his class, and probably it is well that it is so, but he showed himself sincere and honest. There were 736 conversions, and in addition about 1,500 have united with the churches.”

A very hard-headed banker told me: “The cost to the city was something over $16,000. The evangelist got over $7,000, but he earned every cent of it. If a lot of preachers in this country would do as much in five years as he did in five weeks, and work half as hard, they might be entitled to as much return.”

A leading editor said: “His sermon on ‘booze’ was I believe, the greatest individual effort I ever heard from the platform. He talked to six thousand men, and held them as in the hollow of his hand. Up in our bindery I understand all the boys and girls were converted and they are sure a happy bunch.”

I know of one mid-Western manufacturing city in which a fervid revival was held by one of the greatest revivalists of the day. It was not a “bad town” in the beginning. It was a “river town,” however—a “liberal town.” The saloons had never been officially closed even under state law of the stringent anti-saloon sort. For a city of 25,000 people it was what is called “wide open.” The revivalist came, and for six weeks his work went on. At the next city election, as a direct result of the revival, the people voted out a “liberal” administration, and voted in a “closed town” administration. The saloons were closed, and the town is so well pleased they are likely to remain closed, for a long time.

I have known Billy Sunday ever since the days when he came to the old Chicago Ball Club, the days when with my athletic ardor yet unabated I was “Chaplain” of the League.

Billy played rattling good ball, championship form, and he has kept the same standard during a phenomenal career. His meetings are enormous in size and results. His “thank offerings” are the largest any evangelist has ever received.

“Drunkenness, gambling, adultery, theatre going, dancing, and card playing are damning America, and nothing can save it from ruin but a revival of religion,’ says Billy Sunday.

“You think, then, that our popular amusements and recreations are wrong?”

I know it. Dancing is nothing but a hugging match set to music. It’s the hotbed of licentiousness whether in a fashionable parlor or in a dive. More girls are ruined by it than by all other things combined. Talk about the poetry of motion! It’s just a devilish snare of souls. Let men dance with men and women with women, and the thing wouldn’t last fifteen minutes. The slum dance is better than the club dance, because they wear more clothes at it.”

“Sow bridge whist and you reap gamblers. The man who sits at a table and bets a thousand on a jack pot is no more a gambler than the society belle who plays bridge for a prize.”

That’s Billy Sunday, America’s greatest evangelist. On the platform he “plays ball.” Attitude, gestures, method—he crouches, rushes, whirls, bangs his message out, as if he were at the bat in the last inning, with two men out and the bases full. And he can go into any city in America and for six weeks talk to six thousand people twice a day, and simply turn that community inside out.

Hannibal Courier-Post. Hannibal, Missouri · Thursday, July 27, 1911

When the Tent Met the Tabernacle: How Chautauqua Shaped Billy Sunday’s Evangelism

In the annals of American religious and cultural life, few figures loom as large—or as loud—as Billy Sunday. Baseball player turned fiery evangelist, Sunday crisscrossed the country in the early 20th century, preaching repentance with the speed of a sprinter and the flair of a vaudevillian. But while his legacy is often associated with revivalism, the DNA of another cultural institution runs unmistakably through his ministry: the Chautauqua movement.

At first glance, Chautauqua and revivalism might seem like distant cousins. One promoted moral uplift through lectures, music, and education. The other sought soul transformation through emotional preaching, altar calls, and fervent prayer. But in the figure of Billy Sunday, these two worlds converged. His campaigns became a kind of hybrid phenomenon: part Chautauqua, part revival, and fully American.

Founded in 1874 on the shores of Chautauqua Lake, New York, by Methodist minister John H. Vincent and inventor Lewis Miller, the original Chautauqua Assembly was conceived as a summer Bible training camp for Sunday School teachers. But it quickly evolved into something broader: a nationwide movement combining education, religion, entertainment, and civic virtue.

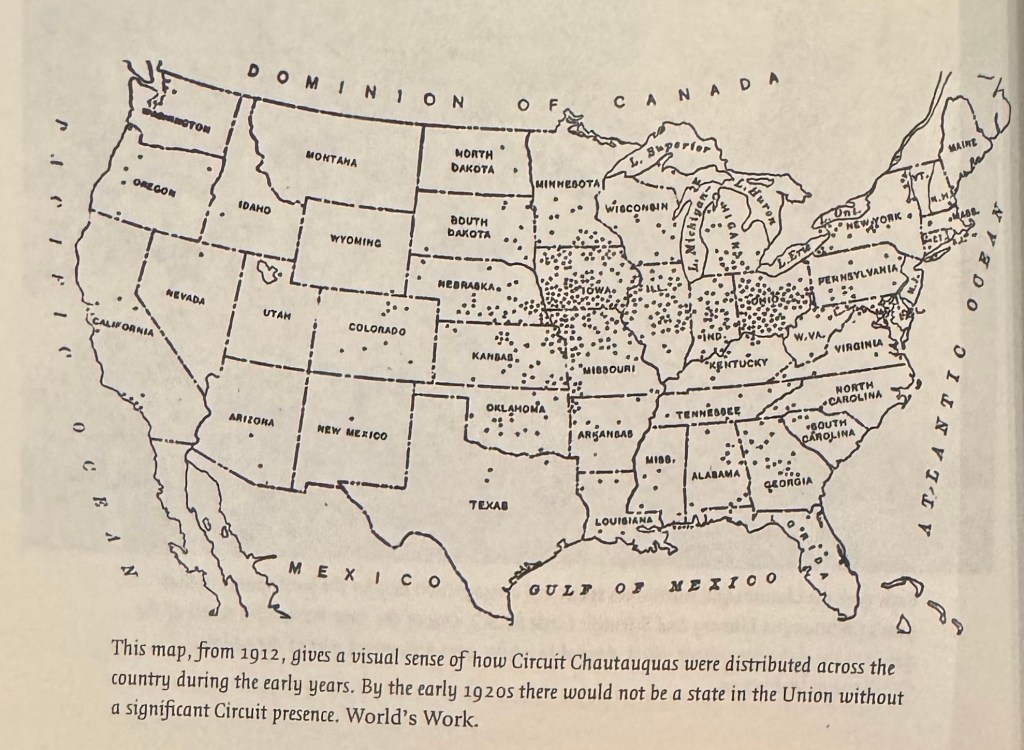

Chautauquas—especially circuit Chautauquas—toured rural America with tents, stages, and full programming that brought lectures, concerts, and clean entertainment to small-town audiences. They celebrated middle-class Protestant values, offering inspiration in digestible, family-friendly form.

By the late 1890s, Billy Sunday had left baseball behind and was learning the ropes of itinerant evangelism. His early mentors, J. Wilbur Chapman and R.A. Torrey, both had connections to the broader Chautauqua scene. Torrey especially was a regular Chautauqua speaker, bringing theology to the people in accessible form.

Sunday’s own gifts—storytelling, humor, physical theatrics, and moral fervor—were tailor-made for the Chautauqua stage. Though he would later distinguish himself through large-scale revivals and sawdust trails, his early career intersected directly with the Chautauqua movement.

One of the pivotal figures behind Sunday’s deeper involvement with the Chautauqua model was Keith Vawter, the mastermind of the circuit Chautauqua system. According to scholar John E. Tapia, Vawter recognized Sunday’s potential to reach mass audiences and personally encouraged him to join the Redpath Chautauqua circuit. Vawter believed Sunday’s electrifying delivery, athletic stage presence, and moral seriousness would resonate strongly with Chautauqua crowds. Sunday accepted Vawter’s invitation in 1910, a move that proved strategic. Through the Chautauqua platform, Sunday expanded his audience, sharpened his performance style, and laid the groundwork for the national revival campaigns that would follow.

Thanks to primary sources and local records, we now know that Billy Sunday didn’t just resemble a Chautauqua speaker—he was one:

Clarinda, Iowa (August 6, 1908) – A postcard written by a local resident records hearing a “Billy Sunday lecture” at the Clarinda Chautauqua. Not a sermon—a lecture. The terminology matters. It shows that Sunday knew how to tailor his message to fit the expectations of a Chautauqua crowd: moral, inspiring, and educational.

Glenwood Park Chautauqua, New Albany, Indiana (c. 1910) – Sunday spoke at this established Chautauqua venue, likely during his period of growing regional fame. He was still accessible to small- to mid-sized communities, many of whom relied on Chautauqua programs to deliver cultural and religious content. Citation source that documents this: New Albany Evening Tribune, July 28, 1911.

Merom Bluff, Indiana (1905–1936 window) – A historical marker affirms that Billy Sunday was among the Chautauqua speakers at this prominent Indiana site, which also hosted Union Christian College and later became a Christian conference center.

Billy Sunday’s campaigns began to take on the structure and tone of a Chautauqua assembly:

Yet Sunday brought something extra—a sense of urgency that Chautauquas, with their genteel tone, typically lacked. He fused the moral inspiration of Chautauqua with the soul-piercing call of revivalism. His tabernacles weren’t just tents for listening; they were arenas for decision.

Chautauquas were formative in shaping expectations for public religious discourse. They taught small-town America that religion could be engaging, moral talk could be entertaining, and spiritual renewal didn’t have to be confined to Sunday morning.

Billy Sunday absorbed this atmosphere. And then he supercharged it.

By the time Sunday’s revivals were drawing tens of thousands in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, they had become national spectacles—but their format still bore the fingerprints of Chautauqua:

His campaigns offered what Chautauqua promised—but with an eternal decision point at the center.

To understand Billy Sunday is to recognize that he wasn’t merely a revivalist in the tradition of Charles Finney or Dwight Moody. He was also a cultural performer in the lineage of Chautauqua. His ministry represents a moment when two great American traditions—moral uplift through public culture and urgent gospel proclamation—merged under one tent.

Billy Sunday didn’t just inherit the Chautauqua model; he transformed it. In doing so, he left behind not only converts, but a new standard for religious communication in the public square: part educator, part entertainer, part prophet.

If you lived in small-town America a century ago and heard that a massive tent was going up just outside of town, you knew exactly what was coming: the Chautauqua was back.

But not just any Chautauqua. This was the circuit Chautauqua—a full-blown cultural caravan, rolling into communities like a blend of TED Talk, county fair, gospel revival, and Broadway road show. It was, as historian Charlotte Canning describes it, “the greatest aggregation of public performers the world has ever known.”

Forget the dusty image of civic lectures and sober-minded schoolteachers. Circuit Chautauquas were performance-driven experiences, intentionally designed to shape the American imagination. They were mobile festivals of ideas, music, drama, and moral vision—staged under a giant canvas tent, and scheduled with industrial precision across the country.

Canning helps us see these not merely as education-on-wheels, but as orchestrated acts of cultural storytelling. At their heart, circuit Chautauquas were about performing a kind of “Americanness”—a staged identity that included democracy, morality, individual responsibility, and civic pride. And these weren’t abstract ideas: they were embodied in actors, lecturers, and musicians who took the platform with everything from Shakespearean monologues to lectures on temperance and suffrage.

The Paradox? These events, often remembered as wholesome and nostalgic, were also deeply commercial. Promoters like Roy Ellison and Keith Vawter didn’t just want to elevate the public—they wanted to make a million. Yet that’s part of the genius: they succeeded in selling culture as spectacle, without cheapening either.

To Canning, the tent was a stage—not just for performers, but for the entire community to see itself. Who belonged? Who was excluded? What did it mean to be an American in 1910 or 1920? Every act—whether musical trio or biblical dramatist—answered those questions in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways.

So the next time you think of rural America in the early 20th century, don’t just imagine plows and porches. Picture the circus-sized tent at the edge of town. The banners. The folding chairs. The packed crowd.

And inside that tent? America on stage.

Resource cited

Charlotte M. Canning. The Most American Thing in America: Circuit Chautauqua as Performance. 2005.

Citation: The South Bend Tribune. Fri, May 16, 1913 ·Page 2

WINONA PLANS FOR GREATEST SUMMER

MANY CONVENTIONS ARRANGED FOR THE SEASON.

BIBLE SESSION FEATURE

William Jennings Bryan, David Lloyd George, Gipsy Smith, “Catch-My-Pal” Patterson and Others Will Speak at Gathering.

The Tribune’s Special Service.

WARSAW, Ind., May 16.—Winona assembly, which will operate this season free from its load of debt, having arranged for the settlement of $300,000 claims by an agreement with the creditors, has prepared for a program of events that will establish a new record. One of the biggest events of the year will be the annual conference of the Church of the Brethren, which will start May 28 and continue until June 7. Between 40,000 to 75,000 churchmen are expected to attend.

The chautauqua program will start June 29 and will continue for 10 weeks. Among the spectacular offerings are the following: Ahasuerus, a sacred opera under the direction of William Dodd Cheney; “The Lost Princess,” under the direction of Mrs. Hortense R. Reynolds; Venetian night, and a great water carnival under the direction of Capt. J. R. Pine. Preparations for the latter event are already under way.

Will Hold Mission School.

Some very notable gatherings are booked to occur during the chautauqua season and at its close. Beginning June 19 and ending June 27, the summer school of missions will be in session. This will be held under the auspices of the interdenominational committee of the assembly. The summer conference of the Presbyterian young people will be held July 9 to 16. The annual meeting of the Ohio Farmers’ Insurance company will be held July 23 and 24. The Health and Happiness club with Mrs. Louise L. McIntyre and Miss Margaret Hall as directors, will be in session July 7 to 14.

The fourth annual conference of the Young Friends of America will be held during the assembly season. The fourth annual session of the international district training school for Sunday school workers will be held Aug. 11 to 21. The Kappa Sigma Pi, the new boys’ movement which was established in 1912 by Homer Rodeheaver, conductor of music for Rev. Billy Sunday, will be in session during July. W. M. Collisson will act as secretary and will be in charge.

Photographers Will Meet.

The 18th annual convention of the Indiana Association of Photographers will meet July 7 to 10. This will be held under the auspices of the National Reform Association. Among the speakers are Dr. James S. Martin, Dr. Lyman E. Davis, Dr. Grant W. Bower, Dr. James McGraw, Ng Poon Chew, of China, Dr. Merle de Aubing, of France, Dr. Armenag of Turkey, and Dr. R. J. Patterson, of Ireland.

One of the big events will be the annual Bible conference, which will be held Aug. 22 to 31. Dr. Sol C. Dickey will be director. He is already busy arranging for the meetings which will bring churchmen here from all parts of the world. Prof. E. O. Excell will have charge of the music and Rev. W. E. Biederwolf will be the assistant director. The opening address will be by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who will also be president of the board of directors of Winona assembly to welcome the visitors. Among the other speakers already engaged are Rev. C. Campbell Morgan, of London; Rev. Gipsy Smith, of Connecticut; Rev. Robert (Catch-My-Pal) Patterson, of Belfast, Ireland, and Hon. David Lloyd-George, chancellor of the British parliament.

The South Bend Tribune. Fri, May 16, 1913 ·Page 2

There seems to be no record of Sunday hosting an evangelistic campaign at Havana, Illinois. This postcard is titled “Billy Sunday addressing 4,000 people at Chautauqua, Havana, Illinois.”

This appearance was part of the broader Chautauqua movement, which brought religious, educational, and cultural programming to communities across the United States.

While Havana isn’t listed among the cities where Sunday held his major revival campaigns, his participation in the Chautauqua there reflects his widespread influence and the popularity of his preaching style. These events often featured prominent speakers and were significant cultural gatherings in early 20th-century America.