In The Man and His Message, Ellis

Evangelist Billy Sunday (1862-1935)

Former professional baseball player-turned urban evangelist. Follow this daily blog that chronicles the life and ministry of revivalist preacher William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (1862-1935)

In The Man and His Message, Ellis

In The Man and His Message, Ellis.

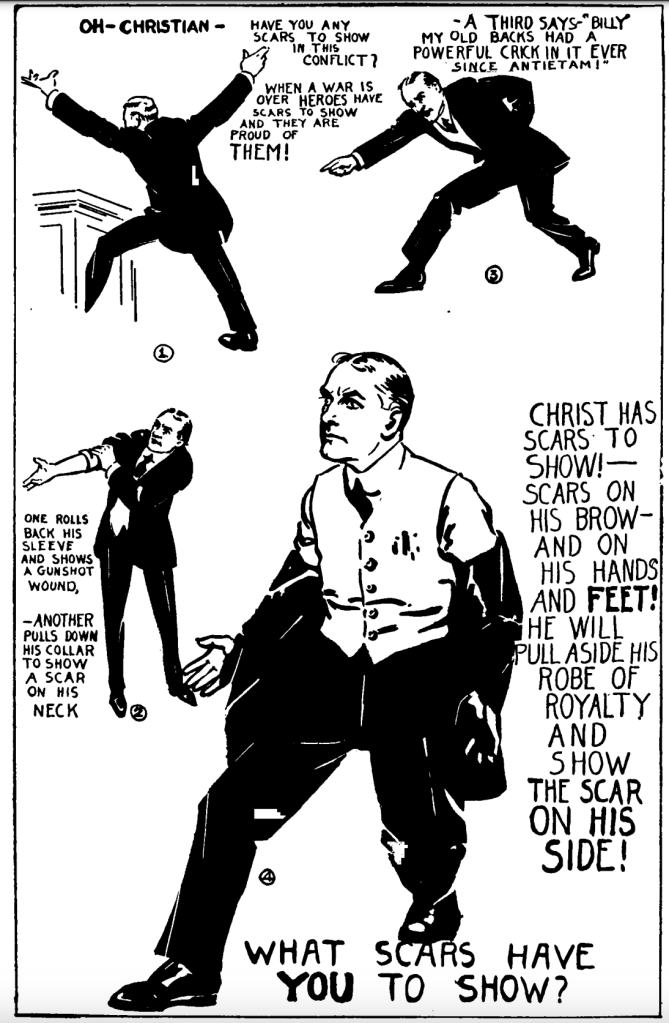

From page 69, Man and His Message, Ellis.

Between 1886 and 1931, Christian publishing houses in the United States offered an unprecedented biographical profile of the contemporary American evangelist as an unambiguously modern figure. Sold at tabernacle tents, Christian bookshops, and church fund-raisers, these texts simultaneously document concerns with the modern landscape as they regale readers with the styles and stories of headlining American Protestants, including Dwight Moody (1837-1899), Sam Jones (1847-1906), Reuben Archer Torrey (1856-1928), J.

Wilbur Chapman (1859-1918), Rodney “Gipsy” Smith (1860-1947), Billy Sunday (1862-1935), and Baxter “Cyclone Mac” McClendon (1879-1935). Although it is not difficult to discern distinguishing marks and regional inflections within the anecdotal particularities of these men, the overarching structure and themes of their chronologies is consistent. The purpose of this essay is to produce the beginning of a collective biography of the turn-of-the-century preacher, highlighting the persistent paradigm represented in the promotional products of these preachers. Whereas previous historians have described these men as antiquated proponents of an “old time” religion, this article argues that their narratives reveal a strikingly modern man, poised in an engaged and contradictory conflict with his contemporary moment.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 June 2018

Religion and American Culture

Evangelist Billy Sunday (1862-1935) is well-known for an aggressively masculine platform style that was clearly aimed at attracting a male audience to his urban revival campaigns. Less recognized but equally important are Sunday’s meetings for “women only,” in which the handsome, athletic evangelist preached passionate, explicit sermons on sexual vice to an audience that had been purged of all male interlopers. Though Sunday’s ostensible purpose was to reinforce traditional Victorian morality-the sermons were originally meant to rail against birth control-the social context for his message subtly undermined its conservative aim. As is illustrated by his campaign in Boston during the winter of 1916-1917, Sunday was perceived by many of his contemporaries, both men and women, as scandalously frank to the point of sexual crudeness. Critics and supporters alike described him in the same terms they used for vaudeville and theater idols, a notion that ex-baseball player Sunday did little to dispel. Yet, evangelical Protestant women came to hear his muscular Christian message anyway. The ability of his female audiences to adapt to—and obviously enjoy— Sunday’s physical stage presence suggests that often-used terms like “feminization” and

“masculinization” are too stark to describe the transition from Victorian to modern forms of religious behavior. Women’s response to Sunday, situated at the intersection of evangelical religion and popular entertainment culture, demonstrates the durability of feminine religious tastes and suggests ways in which the blurring and confusion of formal gender categories factored into the transition from Victorian piety into the more individualized, popularized forms of religious faith in the twentieth century. Women were not passive observers in the transformation of American religion but central to the nature and direction of its survival.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 June 2018

Religion and American Culture

This essay investigates the roles of Billy Sunday’s staff during his urban revivals in the 1910s, especially the committees and departments they administered. Understanding this revival organization is central to understanding Sunday’s success. A corporate organization not only allowed Sunday’s team to reach urban populations, it also put evangelicalism culturally in step with the times. This committee structure made outpourings of the Holy Spirit predictable and even guaranteed, and it helped Sunday create a revivalism for an age of mass production, one that was palatable to a cross-class and nationwide audience and reproducible in cities across the country. Most scholars of American religion are familiar with the outline of Sunday’s career, but the labors of his staff and their contributions remain virtually unexplored. Further, there is a looming historiographical problem with how scholars treat Sunday. His most important years as a revivalist were in the 1910s, before the fundamentalist movement began, but his name is virtually synonymous with fundamentalism. This article challenges scholars to interpret Progressive Era evangelicals not in terms of what they became in the 1920s, but in terms of how they shaped and were shaped by an era of urbanization and consumer capitalism.

Church History

Bureaucracy and Evangelicalism in the Progressive

CONVERTS AND EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA

Millions of Americans watched the evangelist Billy Sunday preach during the years 1905-1935, and many were profoundly affected by the experience. Using letters, published and unpublished reminiscences, and other primary source documents, this article reconstructs the emotional experience of Sunday’s converts and offers insights into the meaning of conversion and followership in Sunday’s and other similar social movements. Through their emotional responses to the evangelist, followers recast socioeconomic problems and community pressures as personal, internal crises that could be resolved through adherence to Sunday’s principles. The process of conversion was considered and volitional; it was also a long-lasting act of self-fashioning. Americans who converted in Sunday’s tabernacles thoroughly reinvented themselves as followers of Sunday and then set out to remake society according to the evangelist’s goals. Generalizing from these insights, the article argues that followership of inspirational leaders was a site of significant agency for Progressive Era Americans. It also identifies emotional experience as a way for historical figures to translate cultural trends into concrete social action. The article concludes by calling for additional research into how emotions shape and condition historical change.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 July 2015

The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era