“Atlanta, Jan. 1.—Ten thousand dollars raised within ten minutes by white citizens of Atlanta yesterday assures the negroes of this city success in completing their Y.M.C.A. building. The white people are pledged to raise another ten thousand if necessary. A fifty thousand dollar fund was needed to obtain the gift of $25,000 from Julius Rosenwald. C.W. McClure made a donation with the statement that the friendly relations between the whites and the negroes were better than ever since Billy Sunday preached to both.”

Jan 1 paper

In the waning days of 1917, as Atlanta turned the page to a new year, a remarkable act of interracial philanthropy unfolded that would leave a lasting mark on the city’s history. Newspapers reported that ten thousand dollars had been raised in just ten minutes by white citizens of Atlanta to help fund a new YMCA building for the city’s Black community. The drive was part of a larger campaign to secure a matching gift of twenty-five thousand dollars from Julius Rosenwald, the Sears, Roebuck & Co. magnate whose generosity was transforming African American education and social life across the South. Local businessman C.W. McClure, who helped spearhead the effort, remarked that the relations between whites and Blacks in Atlanta had improved markedly since evangelist Billy Sunday had preached to both communities during his campaign there.

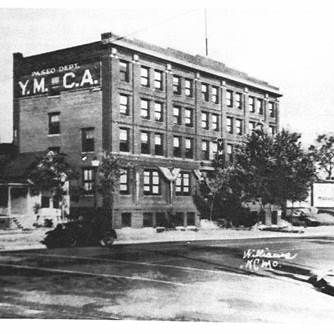

The fruits of that campaign materialized in the Butler Street YMCA—known in its day as the “Negro Y.” Built between 1918 and 1920, the new structure rose in the heart of the Sweet Auburn district, the beating center of Black enterprise and culture in Atlanta. The project followed Rosenwald’s signature pattern: a challenge grant that required local citizens—both white and Black—to raise the balance. The local enthusiasm kindled by Sunday’s revival evidently carried over into civic generosity, helping to meet the $50,000 goal needed to unlock Rosenwald’s contribution.

The Butler Street YMCA quickly became one of the South’s most important centers of African American life. Designed by the firm Hentz, Reid & Adler and built under the direction of Black contractor Alexander D. Hamilton, the facility was impressive for its time—three stories of brick and stone housing a swimming pool, gymnasium, dormitories, meeting halls, and classrooms. It provided a wholesome environment for young men seeking moral and social uplift in a city that offered them few such spaces.

More than a recreational facility, the Butler Street Y grew into a cornerstone of civic and spiritual leadership. Over the decades it came to be known as the “Black City Hall” of Atlanta, hosting meetings that shaped the course of civil rights and community advancement. Figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., Maynard Jackson, and Vernon Jordan would later pass through its doors. The Y stood as a living emblem of what cooperative goodwill and faith-inspired philanthropy could achieve during an era when segregation still divided the city.

The 1918 campaign that launched the Butler Street YMCA was more than a fundraising victory. It was a moment when revival energy turned outward—when the social conscience stirred by Billy Sunday’s preaching translated into practical generosity. In helping to fund the YMCA, the people of Atlanta built not only a structure but also a bridge between communities, one that carried forward the spirit of reform, service, and reconciliation that Sunday’s message had kindled. The Butler Street Y remained for nearly a century a monument to that brief but luminous cooperation—a place where faith met action and where the legacy of revival took tangible form in brick, mortar, and hope.