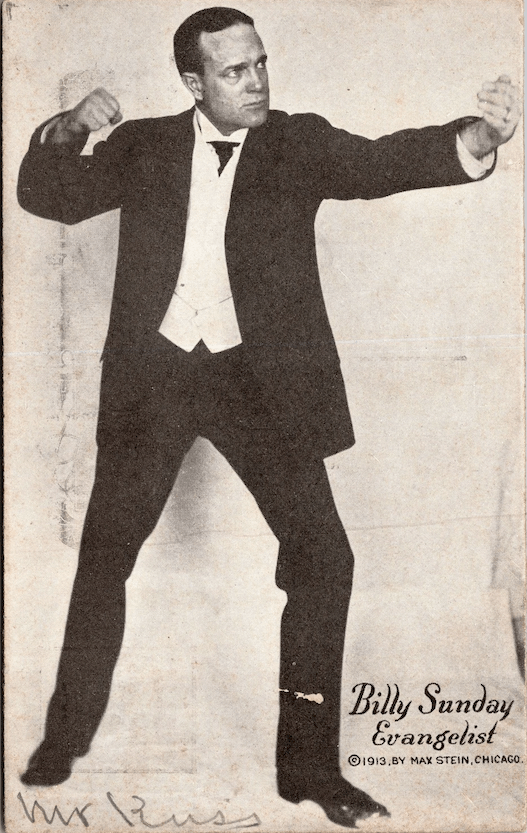

Image source: eBay (late June 2025)

This postcard is postmarked South Bend. Billy held this campaign from April 27-June 15, 1913.

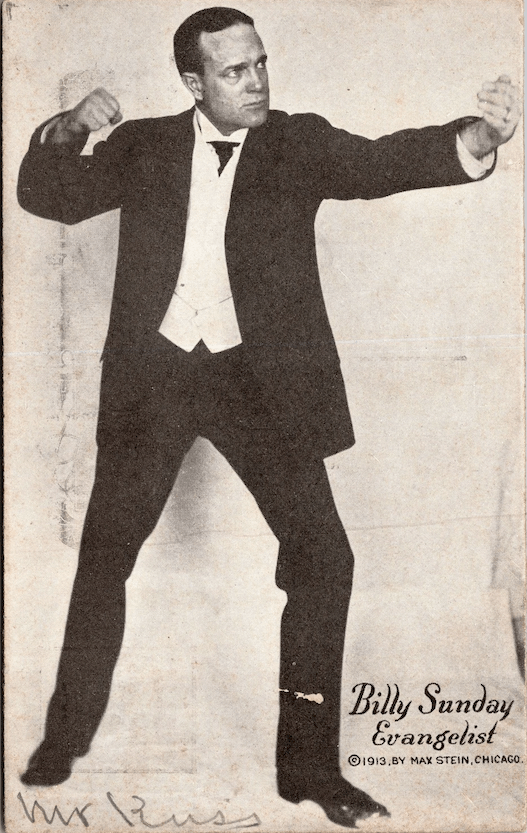

Evangelist Billy Sunday (1862-1935)

Former professional baseball player-turned urban evangelist. Follow this daily blog that chronicles the life and ministry of revivalist preacher William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (1862-1935)

Image source: eBay (late June 2025)

This postcard is postmarked South Bend. Billy held this campaign from April 27-June 15, 1913.

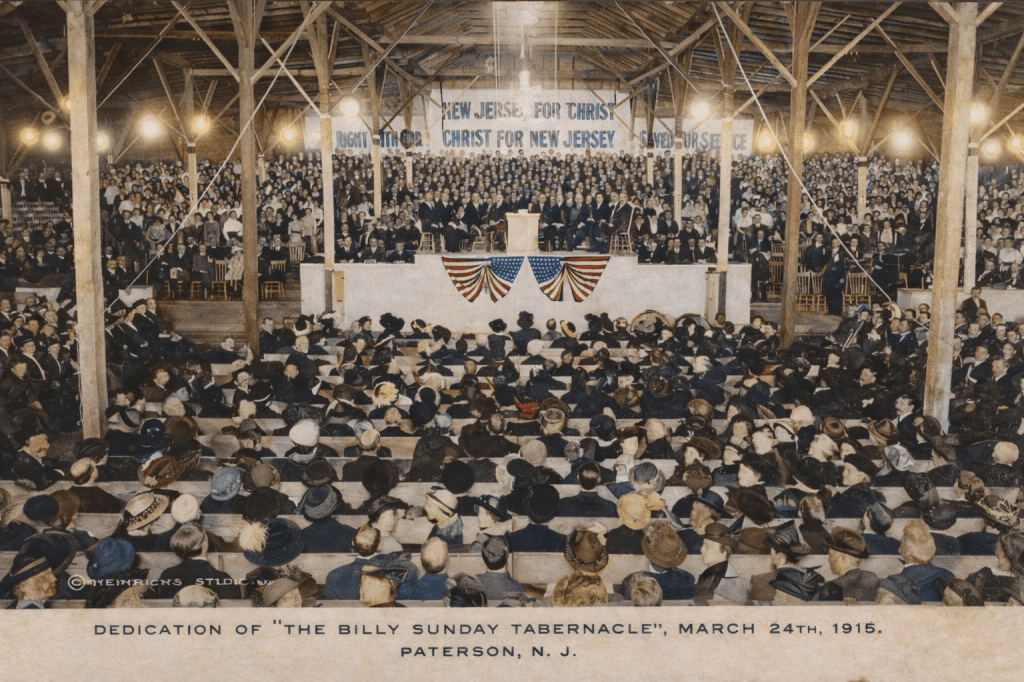

Image source: eBay (late June 2025)

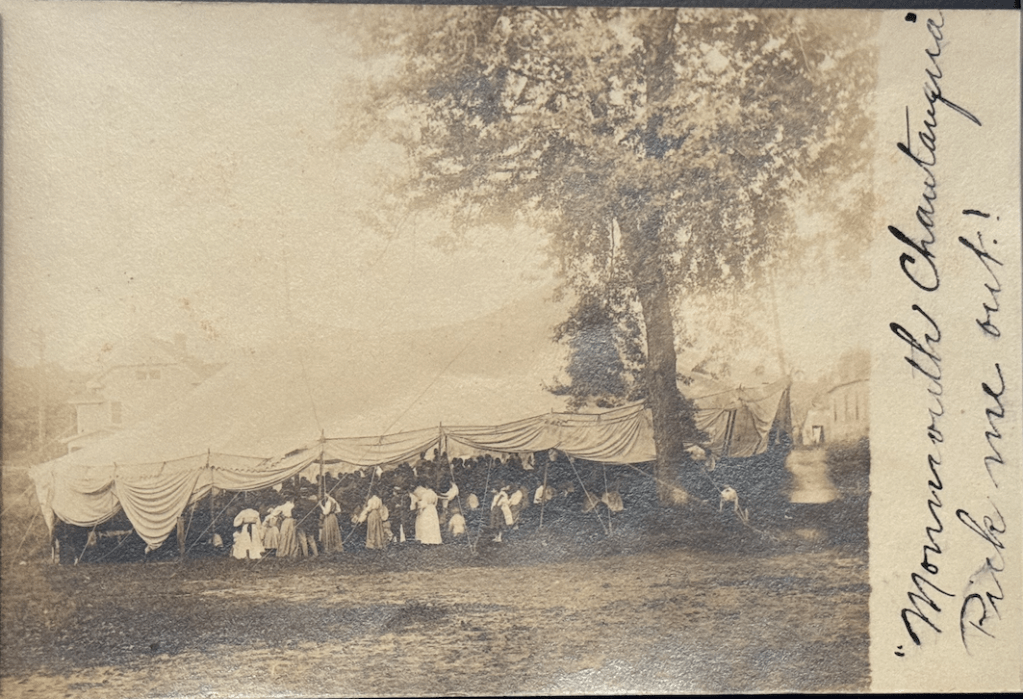

Billy held his Cedar Rapids campaign Oct 10 – Nov 21st 1909

Image source: eBay (Feb 2025), colorized by author

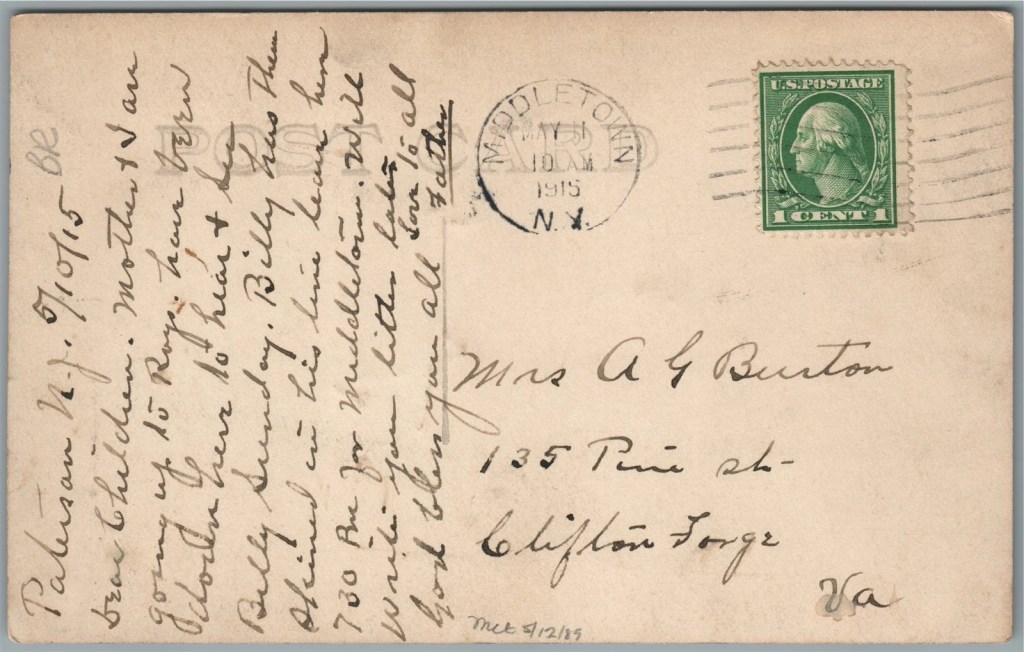

Image source: eBay (late June 2025)

When the Tent Met the Tabernacle: How Chautauqua Shaped Billy Sunday’s Evangelism

In the annals of American religious and cultural life, few figures loom as large—or as loud—as Billy Sunday. Baseball player turned fiery evangelist, Sunday crisscrossed the country in the early 20th century, preaching repentance with the speed of a sprinter and the flair of a vaudevillian. But while his legacy is often associated with revivalism, the DNA of another cultural institution runs unmistakably through his ministry: the Chautauqua movement.

At first glance, Chautauqua and revivalism might seem like distant cousins. One promoted moral uplift through lectures, music, and education. The other sought soul transformation through emotional preaching, altar calls, and fervent prayer. But in the figure of Billy Sunday, these two worlds converged. His campaigns became a kind of hybrid phenomenon: part Chautauqua, part revival, and fully American.

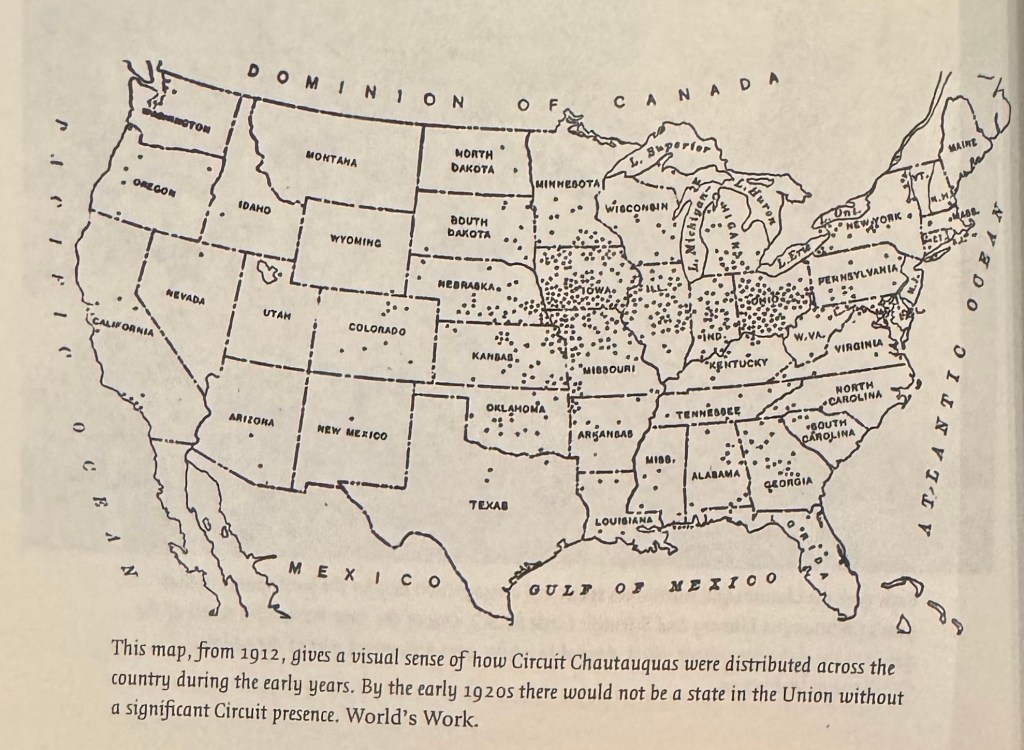

Founded in 1874 on the shores of Chautauqua Lake, New York, by Methodist minister John H. Vincent and inventor Lewis Miller, the original Chautauqua Assembly was conceived as a summer Bible training camp for Sunday School teachers. But it quickly evolved into something broader: a nationwide movement combining education, religion, entertainment, and civic virtue.

Chautauquas—especially circuit Chautauquas—toured rural America with tents, stages, and full programming that brought lectures, concerts, and clean entertainment to small-town audiences. They celebrated middle-class Protestant values, offering inspiration in digestible, family-friendly form.

By the late 1890s, Billy Sunday had left baseball behind and was learning the ropes of itinerant evangelism. His early mentors, J. Wilbur Chapman and R.A. Torrey, both had connections to the broader Chautauqua scene. Torrey especially was a regular Chautauqua speaker, bringing theology to the people in accessible form.

Sunday’s own gifts—storytelling, humor, physical theatrics, and moral fervor—were tailor-made for the Chautauqua stage. Though he would later distinguish himself through large-scale revivals and sawdust trails, his early career intersected directly with the Chautauqua movement.

One of the pivotal figures behind Sunday’s deeper involvement with the Chautauqua model was Keith Vawter, the mastermind of the circuit Chautauqua system. According to scholar John E. Tapia, Vawter recognized Sunday’s potential to reach mass audiences and personally encouraged him to join the Redpath Chautauqua circuit. Vawter believed Sunday’s electrifying delivery, athletic stage presence, and moral seriousness would resonate strongly with Chautauqua crowds. Sunday accepted Vawter’s invitation in 1910, a move that proved strategic. Through the Chautauqua platform, Sunday expanded his audience, sharpened his performance style, and laid the groundwork for the national revival campaigns that would follow.

Thanks to primary sources and local records, we now know that Billy Sunday didn’t just resemble a Chautauqua speaker—he was one:

Clarinda, Iowa (August 6, 1908) – A postcard written by a local resident records hearing a “Billy Sunday lecture” at the Clarinda Chautauqua. Not a sermon—a lecture. The terminology matters. It shows that Sunday knew how to tailor his message to fit the expectations of a Chautauqua crowd: moral, inspiring, and educational.

Glenwood Park Chautauqua, New Albany, Indiana (c. 1910) – Sunday spoke at this established Chautauqua venue, likely during his period of growing regional fame. He was still accessible to small- to mid-sized communities, many of whom relied on Chautauqua programs to deliver cultural and religious content. Citation source that documents this: New Albany Evening Tribune, July 28, 1911.

Merom Bluff, Indiana (1905–1936 window) – A historical marker affirms that Billy Sunday was among the Chautauqua speakers at this prominent Indiana site, which also hosted Union Christian College and later became a Christian conference center.

Billy Sunday’s campaigns began to take on the structure and tone of a Chautauqua assembly:

Yet Sunday brought something extra—a sense of urgency that Chautauquas, with their genteel tone, typically lacked. He fused the moral inspiration of Chautauqua with the soul-piercing call of revivalism. His tabernacles weren’t just tents for listening; they were arenas for decision.

Chautauquas were formative in shaping expectations for public religious discourse. They taught small-town America that religion could be engaging, moral talk could be entertaining, and spiritual renewal didn’t have to be confined to Sunday morning.

Billy Sunday absorbed this atmosphere. And then he supercharged it.

By the time Sunday’s revivals were drawing tens of thousands in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, they had become national spectacles—but their format still bore the fingerprints of Chautauqua:

His campaigns offered what Chautauqua promised—but with an eternal decision point at the center.

To understand Billy Sunday is to recognize that he wasn’t merely a revivalist in the tradition of Charles Finney or Dwight Moody. He was also a cultural performer in the lineage of Chautauqua. His ministry represents a moment when two great American traditions—moral uplift through public culture and urgent gospel proclamation—merged under one tent.

Billy Sunday didn’t just inherit the Chautauqua model; he transformed it. In doing so, he left behind not only converts, but a new standard for religious communication in the public square: part educator, part entertainer, part prophet.

If you lived in small-town America a century ago and heard that a massive tent was going up just outside of town, you knew exactly what was coming: the Chautauqua was back.

But not just any Chautauqua. This was the circuit Chautauqua—a full-blown cultural caravan, rolling into communities like a blend of TED Talk, county fair, gospel revival, and Broadway road show. It was, as historian Charlotte Canning describes it, “the greatest aggregation of public performers the world has ever known.”

Forget the dusty image of civic lectures and sober-minded schoolteachers. Circuit Chautauquas were performance-driven experiences, intentionally designed to shape the American imagination. They were mobile festivals of ideas, music, drama, and moral vision—staged under a giant canvas tent, and scheduled with industrial precision across the country.

Canning helps us see these not merely as education-on-wheels, but as orchestrated acts of cultural storytelling. At their heart, circuit Chautauquas were about performing a kind of “Americanness”—a staged identity that included democracy, morality, individual responsibility, and civic pride. And these weren’t abstract ideas: they were embodied in actors, lecturers, and musicians who took the platform with everything from Shakespearean monologues to lectures on temperance and suffrage.

The Paradox? These events, often remembered as wholesome and nostalgic, were also deeply commercial. Promoters like Roy Ellison and Keith Vawter didn’t just want to elevate the public—they wanted to make a million. Yet that’s part of the genius: they succeeded in selling culture as spectacle, without cheapening either.

To Canning, the tent was a stage—not just for performers, but for the entire community to see itself. Who belonged? Who was excluded? What did it mean to be an American in 1910 or 1920? Every act—whether musical trio or biblical dramatist—answered those questions in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways.

So the next time you think of rural America in the early 20th century, don’t just imagine plows and porches. Picture the circus-sized tent at the edge of town. The banners. The folding chairs. The packed crowd.

And inside that tent? America on stage.

Resource cited

Charlotte M. Canning. The Most American Thing in America: Circuit Chautauqua as Performance. 2005.

How Industrialization, Urbanization, and Moral Upheaval Set the Stage for Revival

When Billy Sunday’s voice rang out across America’s wooden tabernacles, he wasn’t just preaching sermons—he was answering a cultural cry. From 1900 to the early 1920s, the United States was spinning in the whirlwind of transformation. Old institutions were cracking, new cities were rising, and the American soul was searching for an anchor. Into that spiritual vacuum stepped Sunday—a preacher who didn’t just understand the moment; he embodied it.

By the early 20th century, America was moving from farm to factory. In 1870, only 25% of the population lived in cities. By 1920, over 50% did. The dizzying shift from rural life to urban sprawl left many disoriented. Long-standing community structures—churches, front porches, family farms—were being replaced by crowded tenements, anonymous factory work, and the fast pace of modern life. People needed clarity, direction, and moral certainty.

Sunday gave it to them—loudly, plainly, and with baseball-player bravado.

The U.S. was also undergoing its greatest wave of immigration, with over 14 million new arrivals between 1900 and 1920. While these immigrants enriched the nation’s culture, they also stoked fears among native-born Protestants about identity, religion, and national character. Sunday’s revivals, though not overtly anti-immigrant, often appealed to a kind of nostalgic Protestant Americanism that comforted people who felt their world slipping away.

Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution was rewriting the rules of labor and wealth. Robber barons rose; workers organized. Socialist ideas were gaining traction. Against this backdrop, Sunday didn’t call for revolution—he called for regeneration. He told workers to repent, not revolt. He urged bosses to clean up their lives, not just their payrolls. In an age when ideologies were competing to explain human brokenness, Sunday offered the most American answer imaginable: personal repentance and individual transformation.

And of course, moral reform movements were gaining steam—chiefly the push for Prohibition. The saloon had become a symbol of urban vice, immigrant excess, and male irresponsibility. Billy Sunday didn’t just preach against alcohol—he declared war on it. His famous line, “I’m against the saloon with all the power I’ve got,” wasn’t just rhetoric; it helped catalyze a national movement that led to the 18th Amendment.

So why did Billy Sunday rise when he did?

Because he stepped into a nation off balance, morally confused, spiritually hungry, and socially uprooted. He didn’t just ride the wave—he harnessed it. His sermons shouted what many Americans were whispering: that the old truths still mattered, that the Bible still had authority, and that one man’s conviction could still move a crowd.

In an age of massive upheaval, Billy Sunday stood like a lightning rod—conducting fear, hope, outrage, and repentance into one electrifying movement.

I just love this image of Billy Sunday.

It is sitting on this desk upstairs.

Picture use courtesy of The Winona Lake History Center.

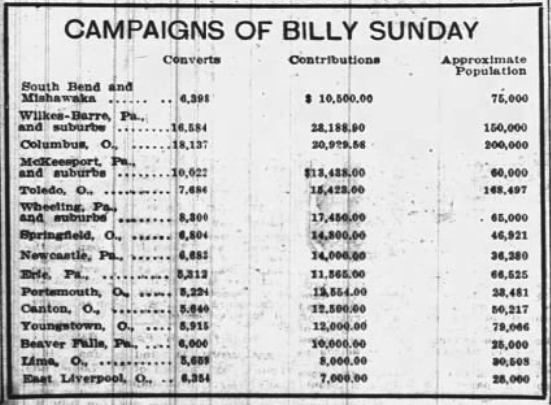

| Location South Bend & Mishawaka Wilkes-Barre, PA Columbus, OH McKeesport, PA Toledo, OH Whelling, PA Springfield, OH Newcastle, PA Erie, PA Porstmouth, OH Canton, OH Youngstown, OH Beaver Falls, PA Lima, OH East Liverpool, OH | Converts 6,391 16,584 18,137 10,022 7,684 8,300 6,804 6,683 5,312 5,224 5,640 5,915 6,000 5,669 6,354 | Contributions $ 10,500.00 $ 28,188.90 $ 20,929.58 $ 13,438.00 $ 15,423.00 $ 17,450.00 $ 14,800.00 $ 14,000.00 $ 11,565.00 $ 12,554.00 $ 12,500.00 $ 12,000.00 $ 10,000.00 $ 8,000.00 $ 7,000.00 | Approx. Pop. 75,000 150,000 200,000 60,000 163,497 65,000 46,921 36,380 66,525 23,481 50,217 79,066 25,000 30,508 25,000 |

South Bend Tribune. Mon, Jun 16, 1913 ·Page 12

Citation: The South Bend Tribune. Mon, Jun 16, 1913 ·Page 12

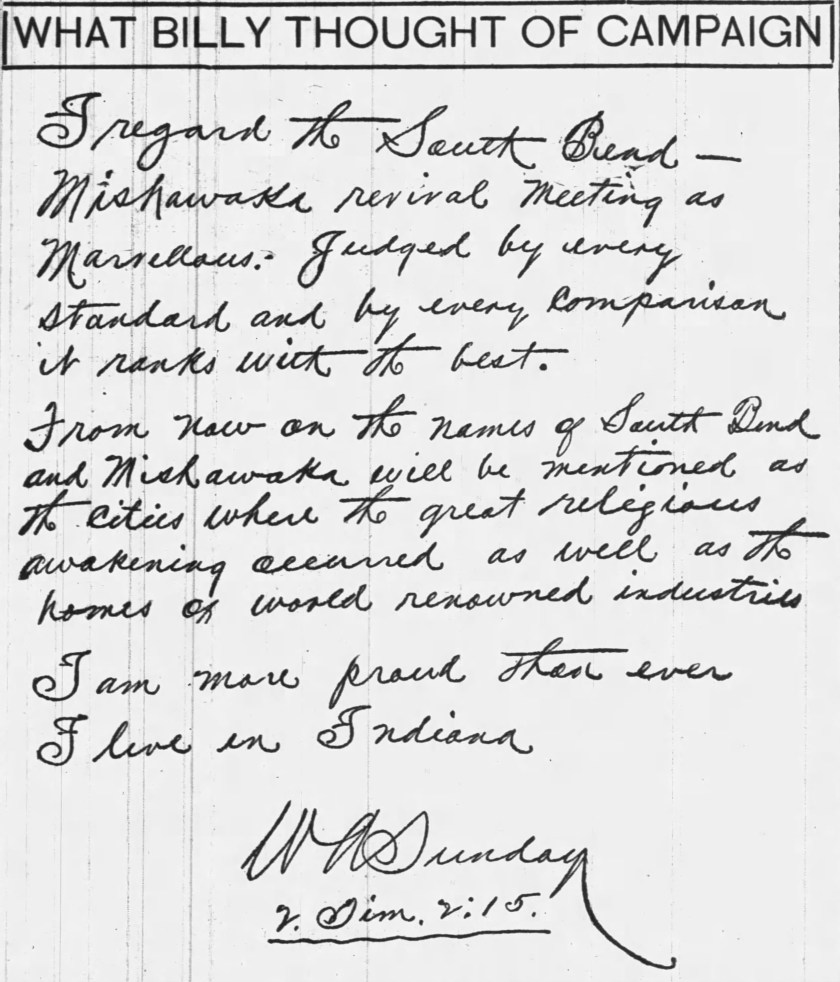

I regard the South Bend – Mishawaka revival Meeting as Marvelous. Judged by every standard and by every comparison it ranks with the best.

From now on the names of South Bend and Mishawaka will be mentioned as the cities where the great religious awakening occurred as well as the homes of world renowned industries.

I am more proud than ever I live in Indiana

Wm Sunday

2 Tim. v:15.

WHAT BILLY THOUGHT OF CAMPAIGN

Citation: The South Bend Tribune. Mon, Jun 16, 1913 ·Page 1

SOUTH BEND’S RELIGIOUS CAMPAIGN PROVES TO

BE MOST NOTABLE IN HISTORY OF ALL INDIANA

AIR OF SADNESS PREDOMINATES AT CLOSING MEETING OF BILLY SUNDAY’S BIG REVIVAL.

“BOSS” AND “MA” SAY THEIR LAST FAREWELL

Hundreds Cheer Evangelist and His Wife on Rear of Car as They Leave City—Other Thousands Disappointed by Early Departure—Last Day of Services Proves to be Remarkable One—Over 30,000 Present.

RESULTS IN BRIEF.

Conversions.

Previous conversions ………. 5,455

Saturday and Sunday ………. 943

Grand total ………. 6,398

Attendance.

Previous attendance ………. 519,550

Saturday and Sunday ………. 46,500

Grand total ………. 566,050

Collections.

Special offering for Billy Sunday ………. $10,500.00

Collections for local institutions ………. 737.98

Fund for campaign expenses ………. 18,500.00

Grand total ………. $24,737.98

The taking of the offering for Billy Sunday was one of the features of the closing day of the campaign. Seventeen or more different people and concerns of South Bend and Mishawaka gave donations of $100. The largest was $200, given by Samuel Murdock, of Lafayette, Ind., one of the owners of the Chicago, South Bend & Northern Indiana railway. The donations of $100, which have been recorded thus far, are from the following: South Bend and Mishawaka Ministerial association; Mrs. George Wyman; Mrs. M. V. Belser; citizens of Kingston, Pa.; by George L. Newell; Folding Paper Box company; Stephenson Underwear mills; E. G. Eberhart; Stephenson Manufacturing company; C. C. Shafer; Col. George M. Studebaker; Mr. Clement Studebaker; a friend; Clement Studebaker, Jr.; J. D. Oliver; Mrs. George Ford; C. A. Carlisle and the Mishawaka Woolen Manufacturing company. The $50 donations, which have been reported to those in charge of the campaign finances, are as follows: Mrs. J. C. Ellsworth; W. O. Davies; F. H. Badet; Mr. and Mrs. W. H. Thompson; J. C. Bowsher; McBrillan & Jackson; S. P. Studebaker and Mrs. Ida M. Stull, and the U. B. Memorial church.

Billy Sunday’s seven weeks’ fight against the devil in St. Joseph county became religious history to-day after the baseball evangelist had shown 6,393 people the road to salvation and approximately $10,500 had been raised for him.

The final curtain was rung down last night and the hard working little evangelist, with his wife, said goodbye to South Bend at 10 o’clock this morning. With a check for the $10,500 tucked away in an inside coat pocket, Billy boarded at 10 o’clock Northern Indiana Interurban car for his home at Winona.

A thousand people saw him off. Hundreds waved their hats and handkerchiefs at the evangelist, his wife, and Rev. William Asher, as the car moved out of the station and down Michigan street. All three stood on the rear platform bowing and smiling in response.

It is estimated a crowd of 8,000 or 10,000 people would have been at the car to say goodbye but the evangelist, leaving an hour earlier than he expected, disappointed many. The Northern Indiana company agreed to run the car through to Winona to insure the evangelist he would be able to eat lunch under his own roof.

State’s Greatest Revival.

With Sunday’s farewell prayer and a general handshaking all around at the tabernacle last night the meetings, which undoubtedly constituted Indiana’s greatest religious campaign, came to a close. The meetings ended quietly and with that heavy solemnity, which told plainer than words what it meant to the people to bid farewell to “Billy,” “Mr.” Ready, “Mac,” Ackley and all the rest.

Tears started in the eyes of many a man, and many a woman, as farewells were said on the platform. Hundreds crowded near the revival leaders to shake their hands and the number to about Homer Rodeheaver, director of the great chorus of 1,000 voices became so large, the people had to be formed in a line and were compelled to move rapidly as soon as they had said goodbye.

Completely worn out, Mr. and Mrs. Sunday were conducted from the tabernacle without notice to the eager thousands, who wanted one more glimpse last word of farewell. The evangelist was forced to permit, however, because of his weakened condition, to leave the building as soon as possible.

[Much more coverage in this issue.]