Part 1: A Nation in Turmoil and Transition

How Industrialization, Urbanization, and Moral Upheaval Set the Stage for Revival

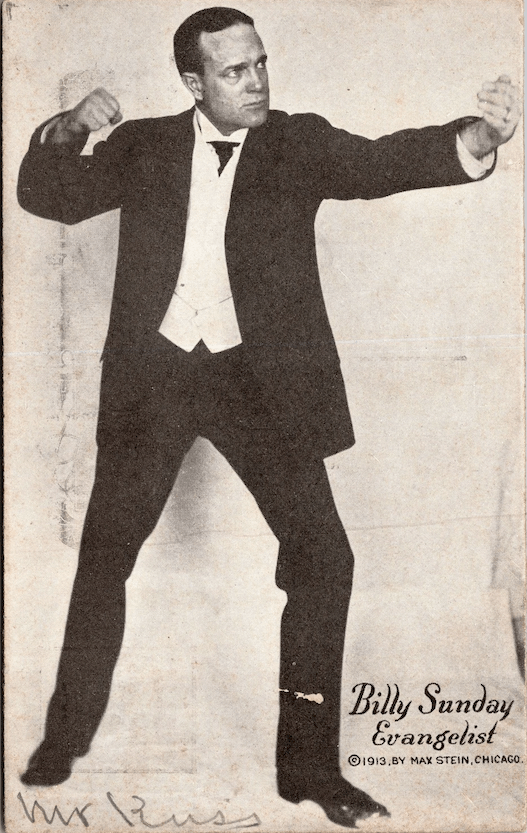

When Billy Sunday’s voice rang out across America’s wooden tabernacles, he wasn’t just preaching sermons—he was answering a cultural cry. From 1900 to the early 1920s, the United States was spinning in the whirlwind of transformation. Old institutions were cracking, new cities were rising, and the American soul was searching for an anchor. Into that spiritual vacuum stepped Sunday—a preacher who didn’t just understand the moment; he embodied it.

By the early 20th century, America was moving from farm to factory. In 1870, only 25% of the population lived in cities. By 1920, over 50% did. The dizzying shift from rural life to urban sprawl left many disoriented. Long-standing community structures—churches, front porches, family farms—were being replaced by crowded tenements, anonymous factory work, and the fast pace of modern life. People needed clarity, direction, and moral certainty.

Sunday gave it to them—loudly, plainly, and with baseball-player bravado.

The U.S. was also undergoing its greatest wave of immigration, with over 14 million new arrivals between 1900 and 1920. While these immigrants enriched the nation’s culture, they also stoked fears among native-born Protestants about identity, religion, and national character. Sunday’s revivals, though not overtly anti-immigrant, often appealed to a kind of nostalgic Protestant Americanism that comforted people who felt their world slipping away.

Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution was rewriting the rules of labor and wealth. Robber barons rose; workers organized. Socialist ideas were gaining traction. Against this backdrop, Sunday didn’t call for revolution—he called for regeneration. He told workers to repent, not revolt. He urged bosses to clean up their lives, not just their payrolls. In an age when ideologies were competing to explain human brokenness, Sunday offered the most American answer imaginable: personal repentance and individual transformation.

And of course, moral reform movements were gaining steam—chiefly the push for Prohibition. The saloon had become a symbol of urban vice, immigrant excess, and male irresponsibility. Billy Sunday didn’t just preach against alcohol—he declared war on it. His famous line, “I’m against the saloon with all the power I’ve got,” wasn’t just rhetoric; it helped catalyze a national movement that led to the 18th Amendment.

So why did Billy Sunday rise when he did?

Because he stepped into a nation off balance, morally confused, spiritually hungry, and socially uprooted. He didn’t just ride the wave—he harnessed it. His sermons shouted what many Americans were whispering: that the old truths still mattered, that the Bible still had authority, and that one man’s conviction could still move a crowd.

In an age of massive upheaval, Billy Sunday stood like a lightning rod—conducting fear, hope, outrage, and repentance into one electrifying movement.