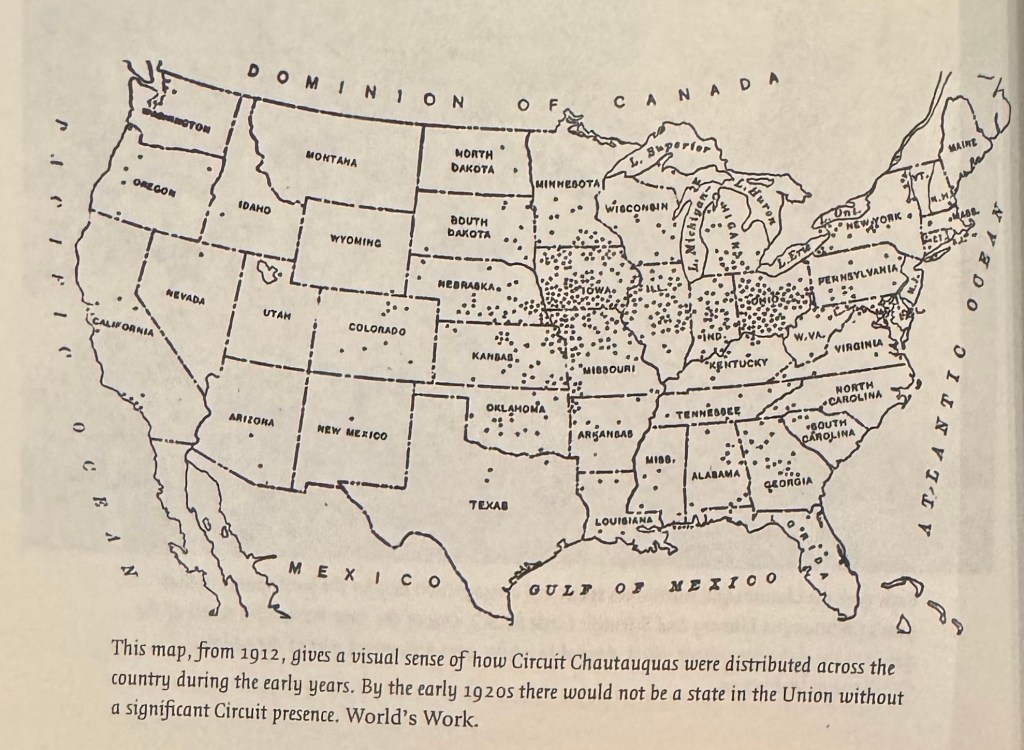

If you lived in small-town America a century ago and heard that a massive tent was going up just outside of town, you knew exactly what was coming: the Chautauqua was back.

But not just any Chautauqua. This was the circuit Chautauqua—a full-blown cultural caravan, rolling into communities like a blend of TED Talk, county fair, gospel revival, and Broadway road show. It was, as historian Charlotte Canning describes it, “the greatest aggregation of public performers the world has ever known.”

Forget the dusty image of civic lectures and sober-minded schoolteachers. Circuit Chautauquas were performance-driven experiences, intentionally designed to shape the American imagination. They were mobile festivals of ideas, music, drama, and moral vision—staged under a giant canvas tent, and scheduled with industrial precision across the country.

Canning helps us see these not merely as education-on-wheels, but as orchestrated acts of cultural storytelling. At their heart, circuit Chautauquas were about performing a kind of “Americanness”—a staged identity that included democracy, morality, individual responsibility, and civic pride. And these weren’t abstract ideas: they were embodied in actors, lecturers, and musicians who took the platform with everything from Shakespearean monologues to lectures on temperance and suffrage.

The Paradox? These events, often remembered as wholesome and nostalgic, were also deeply commercial. Promoters like Roy Ellison and Keith Vawter didn’t just want to elevate the public—they wanted to make a million. Yet that’s part of the genius: they succeeded in selling culture as spectacle, without cheapening either.

To Canning, the tent was a stage—not just for performers, but for the entire community to see itself. Who belonged? Who was excluded? What did it mean to be an American in 1910 or 1920? Every act—whether musical trio or biblical dramatist—answered those questions in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways.

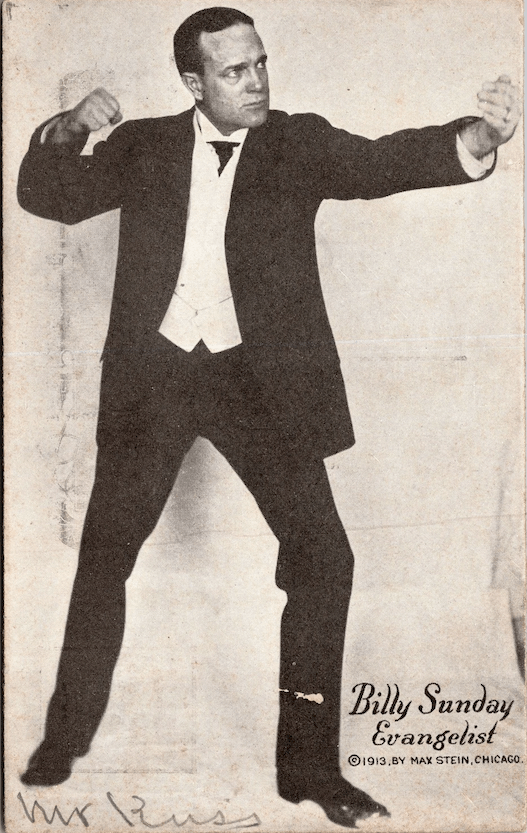

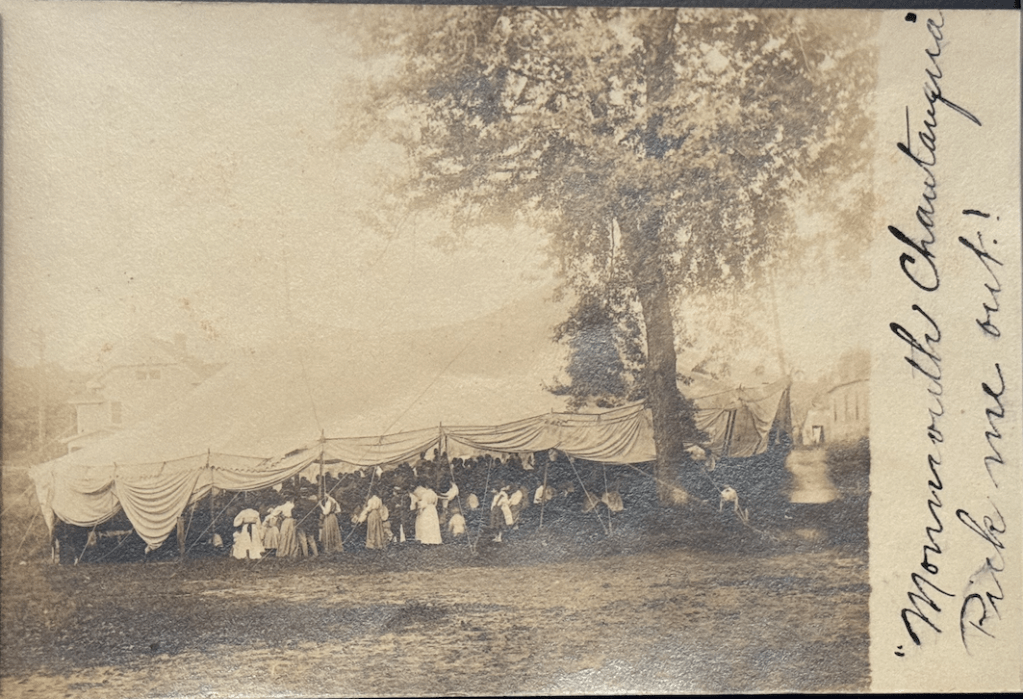

Billy spoke at Monmouth, August 17, 1906.

So the next time you think of rural America in the early 20th century, don’t just imagine plows and porches. Picture the circus-sized tent at the edge of town. The banners. The folding chairs. The packed crowd.

And inside that tent? America on stage.

Resource cited

Charlotte M. Canning. The Most American Thing in America: Circuit Chautauqua as Performance. 2005.