This image is in the public domain.

In early 1911, the city of Toledo, Ohio, found itself at the center of a spiritual and cultural whirlwind when Billy Sunday brought his revival campaign to town. Running from January 29 to March 12, this six-week crusade marked a significant moment not just in Sunday’s ministry, but in the broader urban revival movement sweeping America in the early 20th century.

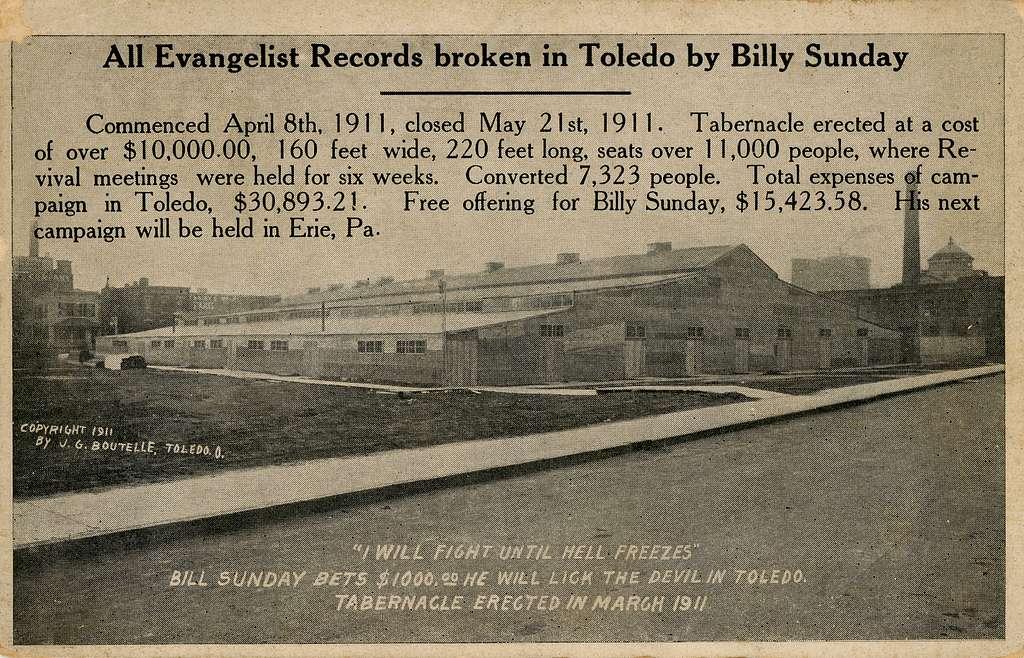

To accommodate the expected crowds, a massive wooden tabernacle seating around 9,000 was constructed along Jefferson Avenue, near downtown. Though the city’s population at the time was just under 170,000, more than 350,000 people flooded into the tabernacle over the course of the campaign. It was not unusual for Sunday to preach three or four times a day to packed audiences, some standing in the aisles or spilling outside the structure just to hear his voice thunder through the open air.

Sunday’s preaching style in Toledo was vintage Billy—fiery, theatrical, and unforgettable. He ran across the stage, leapt onto chairs, punched the air, and peppered his sermons with vivid imagery and baseball metaphors. Among the messages he delivered were some of his most iconic: “Booze,” “Backsliding,” “If Hell is a Joke,” and “The Ten Commandments.” His attack on the saloon business in “Booze” especially struck a chord in a city known for its proliferation of taverns and political corruption. “I want to preach so plainly,” he declared, “that the man who runs may read, and that even the saloonkeeper will know that I mean him!”

The results were staggering. Over 18,000 individuals reportedly made decisions for Christ, and local churches saw a dramatic uptick in attendance and membership. The spiritual momentum didn’t stop at the altar. Sunday’s relentless promotion of Prohibition, moral reform, and church revitalization left an indelible mark on Toledo’s civic and religious landscape.

The local press—especially The Toledo Blade—covered the revival extensively, offering daily summaries and commentary. While some editorials criticized Sunday’s bluntness and emotionalism, many praised the campaign’s influence on the moral climate of the city. Business leaders, city officials, and pastors saw firsthand the social power of mass evangelism, and Sunday’s reputation as a national revivalist soared.

Toledo was more than a successful campaign—it was a turning point. It proved that Sunday could handle large urban centers with complex political, economic, and moral challenges. It set the stage for even bigger crusades in Detroit, Boston, and New York, and solidified his status as one of the most influential evangelists of his time.