BILLY SUNDAY. 71 and PENNILESS. MUST TAKE PLATFORM AGAIN

Once great wealth of evangelist gone in donations to children and strangers; now, old, wearied and sick, he renews exhortations to “hit sawdust trail”

By Henry George Hoch

DETROIT, MICH., Aug.

Broken in health and fortune, Rev. William A. (Billy) Sunday, most effective and spectacular evangelist of the age, is writing a tragic closing chapter in an eventful, glamorous life.

A few years ago, a popular idol, he was wealthy, as most men count wealth. Today, after years of success and affluence, he must traipse a weary, worn-out body about the land because fate has stripped him of his last penny and left him with obligations he didn’t make, but feels he must fulfill.

Neither hardship nor poverty is a stranger to Billy Sunday. Born in a log cabin, he had to start digging for himself when he was six. He knew the bitterness of an orphan’s home. He had to work for most of his education. He’s been “on his own” since he was a stripling.

Billy was born Nov. 19, 1862, in a ramshackle two-room cabin on a 160-acre farm in Story County, near Ames, Ia.

His father, a brick and stone mason who built some of the first brick buildings in Des Moines, had marched away in August, a volunteer in Company E, 23d Iowa Infantry. Billy was a few days more than a month old when word came to the farm of his father’s death.

Billy has been denied even the privilege of saying a prayer at his father’s grave, for a diligent search has failed to reveal its location. Not long ago, however, he received a touching tribute from his father’s old comrades. When he arrived at Des Moines some time ago to hold a campaign, he was met at the train by the thirteen living members of Company E. At their head was the flag they had carried in the Civil War, taken from the state house for the first time since the war, by special permission.

The Sundays were widely known and highly respected in Story County, but they were anything but well off. Billy’s grandfather, “Squire” Corey, at one time owned large tracts of land and helped found the institution that now is Iowa State University, a cousin of Gen. Grant. “Squire” received an invitation to visit him at the White House when he became president of the United States.

“But he didn’t go,” Billy recalled a short time ago. “You know, he was just an Iowa hill Billy, and he thought he’d better stay home where he belonged.”

Billy’s widowed mother did her best to keep her three boys at home, but the wolf was close to their door, and at 8 years of age he had to start running errands and doing odd jobs to help along the family income. Of course, it wasn’t all work and no play, and Billy had a game he liked immensely.

“I used to make a ball of string and cover it with strips I’d tear from mother’s old dresses. Then, when I was going after the cows, I’d toss it way up in the air, close my eyes and run, and then try to find it and catch it,” he recalled.

“When I was just a kid I used to play on a grown-up ball team because I could play better than any of them. They’d wait for me to come to them. I was the only one that knew how to go after it.

Billy was 9 when his mother finally had to give up the struggle to keep the little home together, and he and his older brother, Edward, were packed off to the Soldiers Orphans Home at Glenwood, Ia.

Thousands upon thousands throughout the land have heard Billy tell the story of that trip. His mother was so poor she lacked the money to pay their fare all the way, and the two little boys had to beg a meal at Council Bluffs and then “bum” a ride on a freight train for the last twenty miles to Glenwood.

It was years later that Billy and his mother were reunited, when he was a successful and famous evangelist. She lived with him the last 30 years of her life in the rainy days when he could do more for her materially than she ever had been able to do for him.

The brothers stayed at orphanages, first at Glenwood and then at Davenport, five years. Edward then had reached the age limit of 14, and when he was dismissed, the fourteen-year-old Billy left with him.

For a time they lived with their grandfather “Square” Corey, on his farm near Ames. But Billy didn’t take to farm life, and soon, after an undeserved tongue lashing over a broken yoke, he went to Nevada, Ia., to make his own way in the world.

His first job, in a hotel, gave him board and room. “I was bellhop, bus boy, clerk and everything else. Every morning at 5 o’clock I had to meet the train bulletin: Welton Hotel, dollar a day,” he remembered.

It wasn’t much of a job but it was one of the most important he ever had. Baseball still remembers his speed after more than 40 years, and millions have marveled at his speed on a tabernacle platform. That first job helped him develop it.

“The man who ran the hotel had a mare, and he was mighty proud of her. Every afternoon I had to trot that mare all over town to show her off. I got so I could run her off her feet. And I got so I could run 100 yards without taking a breath,” he declared.

After he lost that job, for staying away an extra day when he’d gone to visit his grandfather, Billy got another doing chores for Col. John Scott, at one time lieutenant governor of Iowa. That job enabled him to return to school and graduate from high school. His ball playing on the high school team made him one of the most widely known youngsters.

A volunteer fire department had much to do with getting Billy into professional baseball.

“All the towns had volunteer fire departments in those days, and they wanted men that could run fast,” he recalled. “They used to hold state tournaments to locate the speedy fellows. I was one of the contests and was asked to come to Marshalltown to join the fire department.

“We had a team at Marshalltown that could pull a 325-pound wagon 300 yards and attach the hose, all in 34 seconds,” he said.

Of course, young Elly got on the Marshalltown built team, and a big time at it, his speed and his ability to get the hard ones made him the star of the team.

“Once we played Des Moines for the state championship and $50 on

the side. We beat them 15 to 4, and I made six of those fifteen runs. I was playing center field, but I had to play left field, too, because the left fielder was drunk.

Ball playing like that made Billy the talk of the town, and, when ‘Pop’ Anson of the Chicago White Stockings, a Marshalltown boy, came home on time for a visit, his aunt told him he ought to ‘look over that Sunday kid.’ ‘Pop’ did, and, in 1884, when he was 22, Billy jumped straight from

the sandlots to the majors. He had several years there and if he hadn’t got religion his speed and pep and natural bent for the dramatic might have made him as much of a gate attraction as Babe Ruth with his brain and bat.

Pop Anson once said that Billy was a bit weak on the hitting side and not the smartest base runner in the game, but a brilliant fielder, a strong and accurate thrower, and one of the fastest men in the game.

There never was a speedier man on the diamond, nor one who liked to take longer chances. One of the fast men in the country to do 100 yards in ten seconds, Billy was the first man to circle the diamond in fourteen seconds “from a standing start, and touching all the bases.”

“No one ever beat that,” he declared recently, with pardonable pride. “Not even Ty Cobb, and he was the greatest baseball player that ever lived.”

Billy wanted more education and while he was with the old White Stockings he attended Northwestern University after the season closed. He had a winter job there coaching the football and baseball teams. Billy was not what you could call a hard drinker, but he used to take a little beer or wine with the boys now and then.

One night in 1887 he was in a downtown Chicago saloon with some other players—among them Mike Kelly and Ed Williamson—when a group from the Pacific Garden Mission started an outdoor meeting at State and Van Buren Streets, near by. Their hymns caught Billy’s attention and interest.

“I used to hear those hymns in Sunday school at home. I’d never heard another sing them. When one of the workers came into the saloon and invited us to attend their meeting at the mission I decided to go. The fellows laughed at me but I went. And I liked it. “I wasn’t converted that night.

But I liked their meetings and I went back several times. One night when Harry Monroe was preaching I found my way to God,” is Billy’s story of his conversion.

Many years later he was to repay in big measure his debt to the mission where he was converted.

Billy didn’t quit baseball immediately after his conversion but he joined the church and became an active worker. And baseball teams had to get along without him when he tore loose on a preaching star. He used to get frequent calls from Y. M. C. A.’s and other men’s groups to lead services and preach, both at home and on the road. He always responded and the novelty of hearing a diamond star deliver a sermon attracted big crowds and got him a lot of attention.

It was in Sunday school Billy first met Nell Thompson, whom millions in America know as “Ma” Sunday. It was love at first sight for him, but she had another beau, and Billy’s suit didn’t progress with the speed with which he circled the bases. Her family didn’t like the idea of her getting too thick with a ball player, either, and at the time forbade her to see him. But Billy was persistent, and soon he began to get a little encouragement. Finally, they overcame the family’s disapproval, and were married.

In the spring of 1891, the Brotherhood Association, forerunner of the American League, broke up and the market was flooded with players.

Billy got his release, and with a wife and baby to support, he left a job which paid him good money to become the first “Y” religious secretary in the country at $1,000 a year.

The Pittsburgh team, to which he had been transferred wanted him back to finish the season. Those weren’t the days of big money in sports, but they offered him $2,500, then $3,500 and finally told him, ‘name your own price.’

But Billy stuck to his $1,000-a-year job, organizing the religious activities of the Chicago Y. M. C. A. and doing the preaching himself now and then.

One of the men he frequently called on for help in these services as song leader was J. Wilbur Chapman, noted evangelist of the ’90s. When Chapman needed an assistant, Billy was recommended, and got the job.

‘I was with Chapman three years. I was his advance man. I put up his tents, took ’em down, sold his books, blacked his shoes—did everything,’ he recalled.

In 1893, while Billy was home for a brief visit with his family, he got a wire announcing Chapman was returning to his old church at Philadelphia.

There was a blow. Billy now had a wife and two children, and neither money nor a job. He and Ma always took their troubles to God in prayer, and they prayed hard and long over that one. Both say what happened is the most convincing answer to prayer they’ve ever had.

It was a letter from Garner, Ia., asking Billy to hold a ten-day revival in their 300-seat opera house. That call always has been a mystery to Billy. So far as he knows, no one in Garner knew him or had heard him preach.

That first campaign was a tough one. Billy, who’d never been on his own before, had to preach at ten meetings, and he had only eight sermons. A lot of midnight oil was burned in Garner before Billy filled the gap.

While that meeting was in progress Billy was invited to hold a campaign at Pawnee City, Neb., and another at Tecumseh, Neb. From that day to this there never has been a day when there weren’t calls ahead for Billy and Ma.

Billy started out with ‘sort of high falutin’ sermons with words as long as your arm, but he soon discovered his real forte, the Anglo-Saxon speech of the man in the street, with plenty of slang and action—the ‘Billy Sunday’ kind of preaching and preaching that nearly everyone in this country has heard, or heard about.

People liked his preaching. His crowds grew bigger and bigger until the Iowa and Nebraska Opera Houses—usually the biggest halls in town—couldn’t begin to hold the crowds, and he had to take to tent meetings.

Constantly the calls kept coming from larger and larger towns, and the middle west was filled with talk of this baseball evangelist who pulled off his coat and vest, tore off his collar and tie, and hopped about like a jumping jack as he blazed away at sin and the devil and booze with salty slang and blunt words never before heard from a pulpit.

There were some who criticized his language, calling it vulgar and out of place, but others talked of how people walked the famous sawdust trail, and how ‘deadbeats’ began to pay their bills after Billy had been in town a few days, and how churches were revitalized after his campaign, and saloons and dens of vice gave way to Y. M. C. A.’s and W. C. T. U.’s and places like that. The cities called to him. He went reluctantly. Elgin, Ill., was the first city to hear him.

“I was scared stiff,” he recalled the other day. “I used to say ‘he done it,’ instead of ‘did it,’ and I got all mixed up on ‘come’ and ‘come.’ But there was a Presbyterian minister there I wish there were more like him today and he took me in hand and helped me.

Billy became a public idol, the talk of the land. His calls took him to nearly every state in the Union, and he has held campaigns in all but four of the major cities of the country. He made his famous sawdust trail and his exhortation, “Get Right with God,” as well known throughout the country as radio today makes a popular tune.

No building was large enough for his city revivals. People used to stand for hours to get seats in tabernacles that would seat from 10,000 to 20,000 persons. One day, in Columbus, O., in 1913 he gave his famous “Women Only” sermon to more than 4,000 women who stormed the 10,000-seat tabernacle there and forced him to hold extra meetings.

During a ten-week campaign in New York he spoke to 1,500,000 people and nearly 100,000 of them hit the trail. His greatest campaigns were held in New York and Chicago in 1917. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was the financial “angel” of the New York meeting.

“He told me, don’t worry about the collections. You won’t have to worry about anything,” Billy said. This Billy Sunday who talked at meeting after meeting from early morning till late at night one New York newspaper estimated he spoke 1,290,000 words in ten weeks of

preaching there was an amazing thing to his old cronies on the ball clubs.

When Billy was in Detroit in the fall of 1933, he renewed acquaintance with Fred E. Goldie Goldsmith. They had been teammates on the old Chicago White Stockings in the ’80s, when that team came to Detroit and set an all-time record by scoring eighteen runs in one inning. “That Billy Sunday has got to be quite a talker,” Goldie commented. “He was such a quiet lad on the team. Never said hardly anything.”

Other friends have commented on that trait. The man who has preached to greater visible crowds than any other living American, talking generally for much more than an hour, is at heart a silent, retiring man. Away from his work he prefers to let others do the talking.

Through the years of success such as no other evangelist has known, great sums of money passed through Billy’s hands, hundreds of thousands of dollars. Most of it was given away to needy people and institutions. Today, all of it is gone. New York gave him the biggest ‘love offering’ he, or any other evangelist, ever has received.

We had just entered the war when I began my New York campaign,’ he said. ‘The first day of the campaign I told them whatever they gave me I would give to the boys overseas through the Red Cross, the Y.M.C.A., the Salvation Army, and the like.

‘They gave me $120,465, and every penny of it went to the boys over- there. When I left New York I had to draw on my own funds for my railroad fare.’

Chicago also gave him a great offering $65.00, and all of that was given to the old Pacific Garden Mission, in which he had been converted 38 years before.

One of his converts, a former convict, once came to Billy and related the story of losing his home because he couldn’t meet the payments. Billy wrote him a check for $500 to pay off the mortgage.

Friends say he has financed the college education of more than 70 young men and that the country is dotted with homes and institutions that have been helped through dark days by Billy’s checks.

It was about six years ago that the tragic series of events began which he himself has called his worst years. He is on the road, although he needs rest — and wants it.

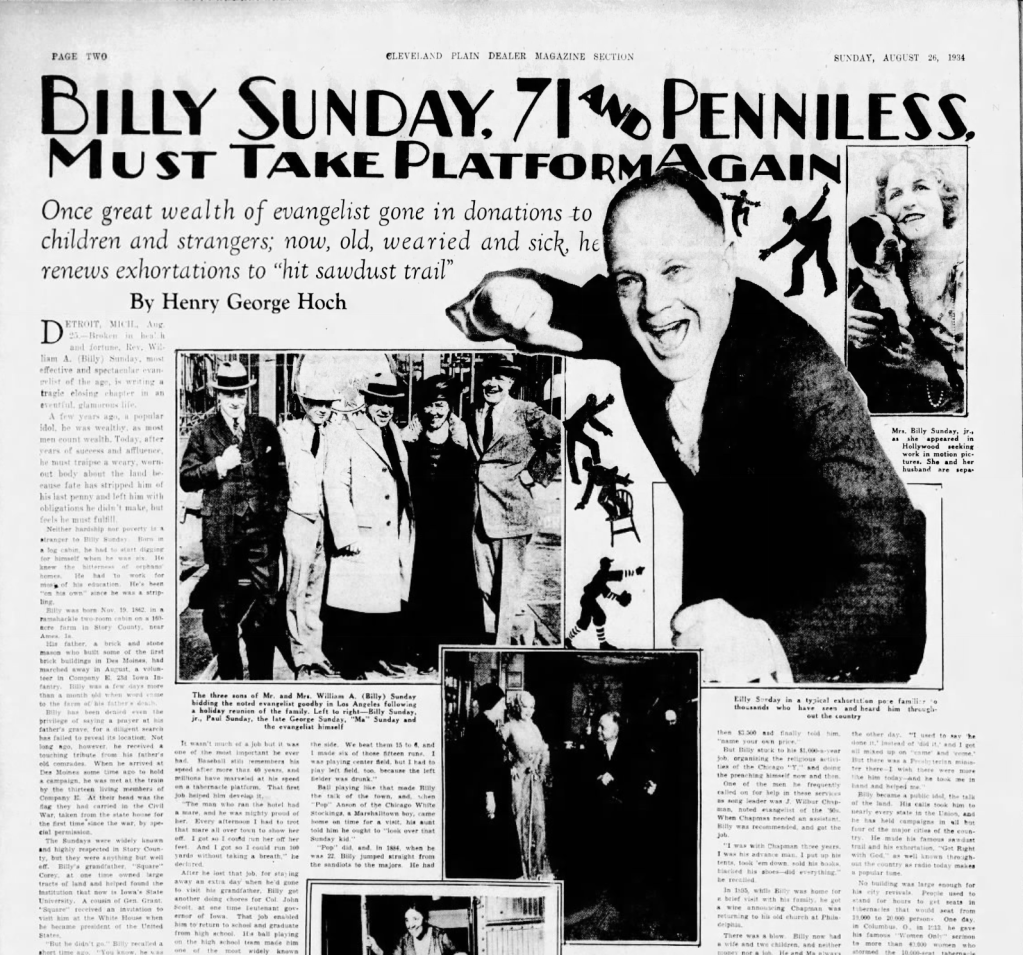

His eldest son, George, had worked with him for a time in his campaigns, but, after his first marriage he had established a real estate business in Los Angeles. His brother, Billy, Jr., was with him. In 1928, Billy, Jr., was sued for divorce by his actress wife. A week later George and his wife parted and she sued for a separation and support.

One October night in 1932 Billy was speaking in Detroit for the Michigan Anti-Saloon League. After the meeting, he received a call that his daughter, Helen, wife of Frank E. Hagan, surgeon of Mich., was about to die. A friend drove him there before she died, and Billy, marked by grief, returned for the remainder of his tour for the Anti-Saloon League.

A year ago he buried George in a grave beside Helen at Sturgis. And in that grave he buried his hopes of retirement and rest.

When the depression came along, George’s business was hard hit, and then he had family trouble. ‘I used the $8000 I’d saved up to try and save his business and help him out of his troubles. It’s all gone, every penny. And now, George is dead,’ he cried, sobbing with his sobs.

Then he revealed that he had pledged to pay George’s two children $15 a month until they are 21—the eldest now is 17.

A year ago February, at Des Moines, he was stricken by a heart attack during a sermon. A blood clot was found in the coronary artery. He had to spend three months in bed, with Ma nursing him back to health. Then three more months of rest.

He needed more rest, but, last September, past his allotted three-score years and ten, he had to take up again the hard grind of the itinerant evangelist, answering, for the first time in his career, calls from individual churches, and returning once again to the smaller towns.

For Billy Sunday is broke because he sacrificed everything for his children. ‘As long as he lives he must work to live and to meet the obligations he has assumed for others.’

Copyright, 1935, by the Plain Dealer Publishing Co. in co-op with American Newspaper Alliance.

Did Billy Sunday Die Penniless? Separating Fact from Fiction

In the twilight of Billy Sunday’s life, the press painted a picture of a once-glorious evangelist now broken in body and fortune. A 1934 article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer claimed that Sunday had been “stripped of his last penny” and was forced to continue preaching out of sheer necessity. But how much of that is true?

Let’s take a closer look at the facts and exaggerations surrounding the closing chapter of one of America’s most dynamic preachers.

What’s Historically Accurate

1. Great Personal Loss

Billy Sunday endured crushing personal tragedies in his later years. His daughter, Helen, died in 1932. Just a year later, his son George died—after financial ruin, a failed marriage, and spiritual drift. These losses left Billy heartbroken and emotionally drained.

2. Radical Generosity

Sunday wasn’t just a fiery preacher—he was known for extraordinary generosity. During his 1917 campaign in New York City, he received a staggering $120,465 love offering—and gave every penny to soldiers and wartime charities. He also gave generously to students, struggling families, and institutions like Pacific Garden Mission (where he himself had been converted).

3. Declining Health

In 1933, Sunday suffered a heart attack while preaching in Des Moines. Doctors discovered a blood clot in his coronary artery and urged rest. He spent months recuperating—but eventually resumed his preaching schedule despite serious health concerns.

4. Humble Return to Small-Town Preaching

In his final years, Sunday no longer drew the massive urban crowds of earlier decades. Instead, he accepted invitations from small-town churches—returning to the kind of humble venues where he began. This wasn’t a forced exile but a sober shift that reflected the times and his own desire to keep preaching.

What’s Probably Exaggerated

| Claim | Analysis |

|---|---|

| “Stripped of his last penny” | Overstated. Sunday had certainly lost most of his wealth by 1934, but he was not destitute. He still owned property in Winona Lake, Indiana, and had the means to travel. |

| “He must work to live” | Partially true. Sunday continued preaching due to personal obligation—particularly to support his grandchildren—but not because he was facing homelessness or poverty. |

| “Broken in health and fortune” | Dramatic tone. He was declining physically, yes—but he still traveled, preached, and maintained a basic household. His condition was serious, but not total ruin. |

| “All of it is gone” (money) | Unverifiable. He likely had very little liquid wealth by the 1930s, but “all” is a strong word. He retained enough assets to live modestly, and continued to support others financially. |

Final Thought

Billy Sunday’s final years were indeed marked by sorrow, sacrifice, and strain—but not by absolute destitution. While the press dramatized his story for emotional impact, the truth is more nuanced: Sunday gave away fortunes, suffered deeply, and kept preaching to the end—not because he had to survive, but because he felt called.

He didn’t die penniless.

He died spent.

“I want to preach until I can’t preach anymore, and then I want to crawl up into the pulpit and die.”

—Billy Sunday