By Kraig McNutt

In the spring of 1906, the city of Freeport, Illinois—nicknamed by some as the “town of beer and pretzels”—became the unlikely stage for one of the most memorable revivals in early 20th-century American evangelicalism. It was led by none other than Rev. William Ashley “Billy” Sunday, the baseball-star-turned-evangelist whose fiery sermons and athletic stage presence would eventually captivate audiences across the country. But in Freeport, his gospel campaign left an impression still remembered more than a century later.

A Tabernacle Rises

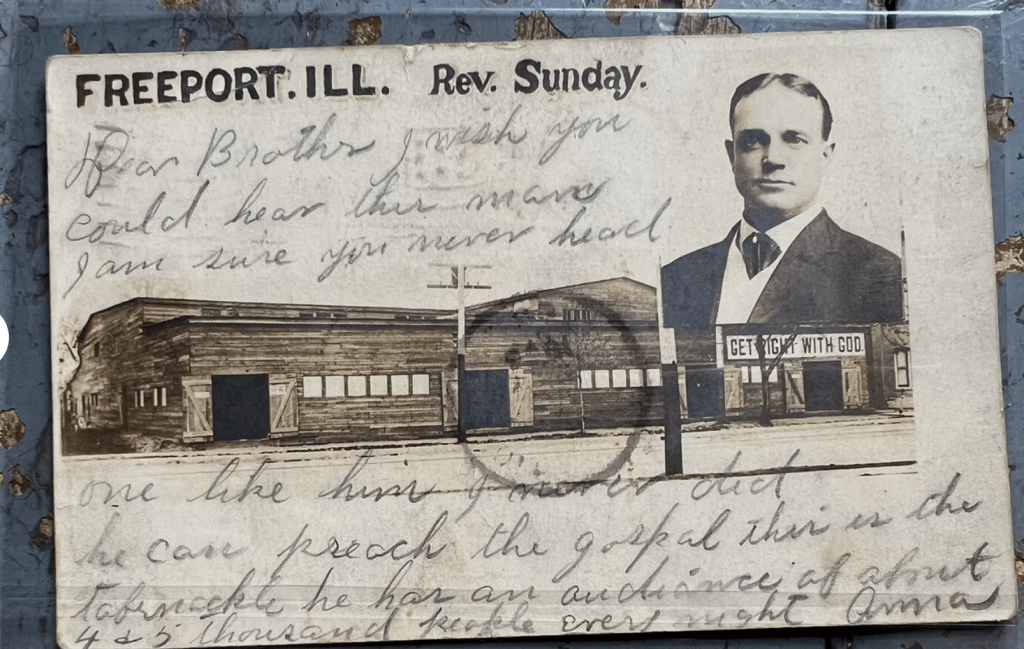

On January 25, The Freeport Journal-Standard announced plans for a wooden tabernacle to be built at the corner of Jackson and Walnut Streets—a temporary structure, 90 by 120 feet, with seating for 2,000. The project, including lumber, lighting, and labor, came with a hefty price tag of nearly $7,000, a bold investment for a campaign that hadn’t even begun.

But the momentum was building. By February, reports described a “revival wave sweeping the state” (Freeport Daily Bulletin, February 17), with Sunday’s campaign seen as the crest of that spiritual tide. Sunday had just completed a campaign in Princeton, Illinois, where 1,890 people—over one-third of the town’s population—had responded to his call for conversion.

Anticipation spread quickly in Freeport. On March 26, area churches agreed not to hold their own meetings during the revival, uniting in support of the citywide effort. By April 4, the Hamlyn Brothers had completed the tabernacle—just in time.

“Hit the Trail!”: Revival Fire Ignites

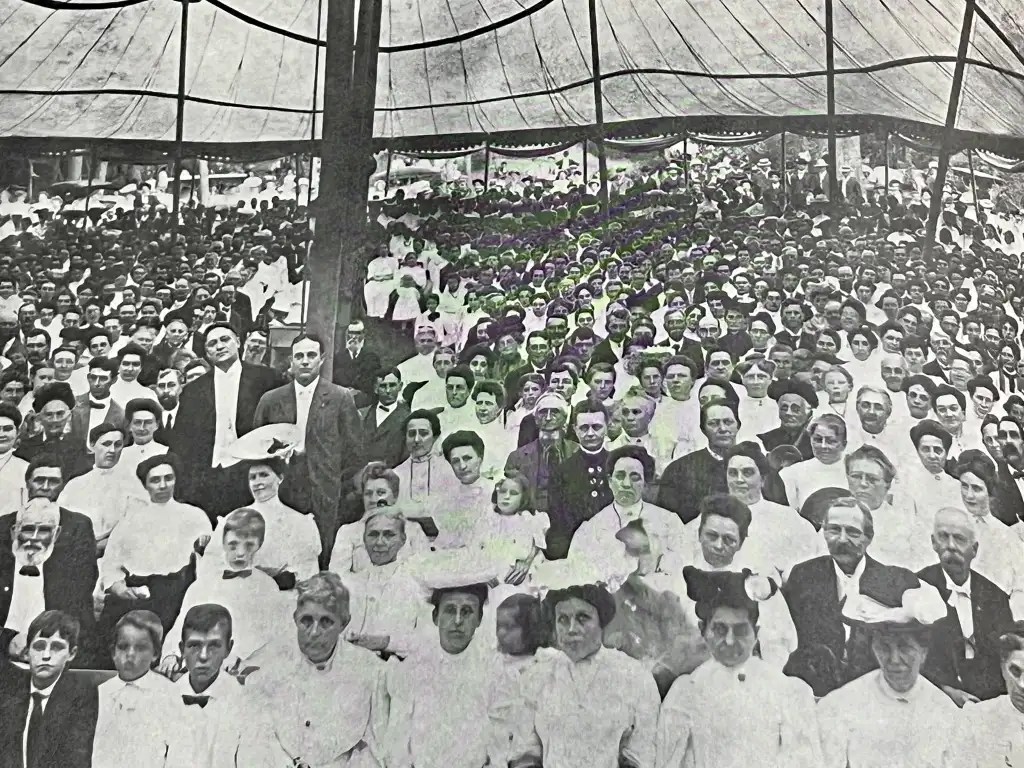

The meetings began on April 28 and were originally scheduled to conclude May 11. But it didn’t take long before city leaders and church officials realized something extraordinary was happening. The campaign was extended through June 3.

Night after night, thousands packed into the tabernacle to hear Sunday thunder against sin and call the city to repentance. By May 22, just eleven days after the originally scheduled end date, 490 conversions had been recorded. Local papers declared the Freeport tabernacle the largest Sunday had ever used at that point in his ministry.

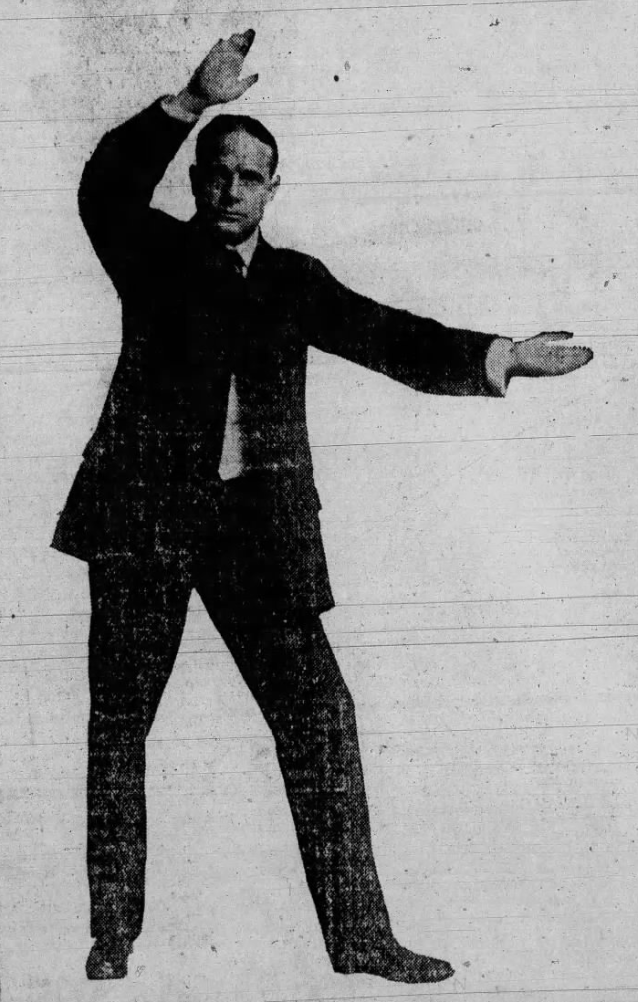

He preached with unmatched energy—sometimes leaping onto the pulpit or running across the stage—and wielded everyday language that even the most skeptical workingman could understand. Sunday brought the gospel to life with baseball metaphors, streetwise illustrations, and all the force of a man who believed eternity was at stake.

“A Lasting Benefit to the City”

The campaign officially ended on Sunday, June 3. Though complete statistics remain elusive, the revival had clearly left its mark. One local newspaper would later reflect that Sunday’s campaign had done “more good than we thought it would” and credited it with producing “better citizens, law-abiding and self-respecting men.”

The same article pointed out that even those who didn’t remain in the church long after the revival had still taken a meaningful step: they had responded, they had come forward, they had heard. “A step in the right direction,” it noted, “builds character.”

Sunday himself moved on to Prophetstown by early July (Freeport Journal-Standard, July 5), but in Freeport, something remained. The revival had galvanized the churches, stirred the consciences of many, and sparked conversations about faith, morality, and public life that would reverberate for months to come.

Beyond Freeport: Sunday’s 1906 Trail of Revival

The Freeport campaign was not the end of Billy Sunday’s evangelistic fire for the year—far from it. Fresh off the sawdust trail in northern Illinois, Sunday continued his whirlwind revival circuit, reaching small towns and stirring hearts across the Midwest and beyond.

Just a month after concluding in Freeport, Sunday preached in Prophetstown, Illinois, in July 1906, continuing to draw crowds eager for his message of repentance and salvation. By fall, he had moved westward to Salida, Colorado, where an unexpected snowstorm destroyed his revival tent. That loss became a turning point in his method: from that point forward, Sunday transitioned away from using large tents and instead began constructing permanent wooden tabernacles—just like the one used in Freeport.

But it was Kewanee, Illinois, in late October through early December of 1906, that demonstrated just how rapidly his influence was growing. Holding a five-week revival in the newly built National Guard Armory, Sunday drew crowds of 2,000 to 4,000 each night, with a staggering 200,000 total attendees reported. So many people flocked to hear him that some had to be turned away at the doors.

Each campaign added to Sunday’s legend, but in many ways, Freeport stood as the hinge moment—a city that proved how a local revival could shake not just individuals but an entire community. And as Sunday’s trail moved on from town to town, the echoes of his voice still lingered in the tabernacle on Jackson and Walnut, where for a few electric weeks in the spring of 1906, revival fire had burned hot in the town of beer and pretzels.

Legacy

Billy Sunday’s Freeport revival was, in many ways, a preview of what was to come. He would go on to preach to millions, become the most prominent evangelist of his era, and leave behind a complex legacy that combined bold preaching with theatrical flair. But in the spring of 1906, before national headlines, before the surge of prohibition politics and radio broadcasts, he stood in a sawdust-covered tabernacle in northern Illinois and offered one simple message: “Choose you this day whom ye will serve.”